Endometrial ablation and resection versus hysterectomy for heavy menstrual bleeding: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness and complications

Article information

Abstract

To evaluate the clinical efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of endometrial ablation or resection (E:A/R) compared to hysterectomy for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. Literature search was conducted, and randomized control trials (RCTs) comparing (E:A/R) versus hysterectomy were reviewed. The search was last updated in November 2022. Twelve RCTs with 2,028 women (hysterectomy: n=977 vs. [E:A/R]: n=1,051) were included in the analyzis. The meta-analysis revealed that the hysterectomy group showed improved patient-reported and objective bleeding symptoms more than those of the (E:A/R) group, with risk ratios of (mean difference [MD], 0.75; 95% confidence intervals [CI], 0.71 to 0.79) and (MD, 44.00; 95% CI, 36.09 to 51.91), respectively. Patient satisfaction was higher post-hysterectomy than (E:A/R) at 2 years of follow-up, but this effect was absent with long-term follow-up. (E:A/R) is considered an alternative to hysterectomy as a surgical management for heavy menstrual bleeding. Although both procedures are highly effective, safe, and improve the quality of life, hysterectomy is significantly superior at improving bleeding symptoms and patient satisfaction for up to 2 years. However, it is associated with longer operating and recovery times and a higher rate of postoperative complications. The initial cost of (E:A/R) is less than the cost of hysterectomy, but further surgical requirements are common; therefore, there is no difference in the cost for long-term follow-up.

Introduction

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics defines heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) as “excessive menstrual blood loss which interferes with a woman’s physical, social, emotional and/or material quality of life” [1]. When other pathology is identified such as leiomyomas >3 cm or adenomyosis, and pharmacological interventions are not preferred or fail to relieve the symptoms, some women undergo surgery [1]. Surgical options, namely hysterectomy or first-or second-generation endometrial ablation or resection (E:A/R), aim at improving the symptoms by endometrial removal or destruction. There is a variety of ablation techniques, such as laser and thermal balloon, all of which target the endometrium. Usage of (E:A/R) has increased as they have several advantages, including fewer complications and shorter recovery times [2–4]. Accordingly, (E:A/R) could be a more cost-effective alternative to hysterectomy if proven to have at least similar effectiveness in reducing the HMB symptoms. To determine the cost-effectiveness, all subsequent costs are considered, including costs of future re-interventions as well as the cost per quality-adjusted life year rather than the isolated cost of the initial procedure [5].

The review by Fergusson et al. [4] revealed that (E:A/R) offers an alternative to hysterectomy as a surgical treatment for HMB. It included 10 randomized controlled trials (RCT) and the quality of studies was low- to moderate-quality RCTs [6]. The review suggested that wider analysis would be valuable and analysis of cost is critical for making healthcare decisions. The Cochrane guideline and protocol states that the reviews should be updated within a 2-year timeframe or provide a commentary justifying that the reasons for non-adherence have been followed [7]. We present this updated systematic review as the last literature search was performed more than 2 years ago. This systematic review aims at presenting an update of the clinically-relevant results with meta-analyses of efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness of (E:A/R) compared to those of hysterectomy for the treatment of HMB.

Methods

All randomized control and quasi-randomized trials, which examined all types and routes of hysterectomy compared to all methods of (E:A/R) with a minimum follow-up duration of 12 months, were included. The included types of hysterectomy were subtotal and total hysterectomy via abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic routes. The methods of endometrial resection (ER) included trans-cervical resection and endometrial ablation (EA), including; thermal balloon, laser, radiofrequency, and microwave. A quasi-randomized trial is a trial in which the participants are allocated to different arms, but the allocation method is not truly random [8]. Meta-analysis was performed as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidance [9] (Supplementary Fig. 1). The eligibility criteria were women: 1) over 18 years old with HMB; 2) having no further desire to conceive; and 3) having a uterine size less than 14 weeks of gestation with no leiomyoma larger than 5 cm. The exclusion criteria were women having: 1) fibroids greater than 5 cm; 2) uterine size over 14 weeks; 3) endometriosis; 4) postmenopausal bleeding; or 5) underlying pathology. These exclusion criteria were set to eliminate other causes of HMB symptoms.

The literature search was last updated in November 2022 using MEDLINE EMBASE Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials, PubMed, Google Scholar, PSYCinfo, and Clinicaltrials.gov (Supplementary Table 1). A manual search of abstract databases of international conferences was performed. There were no restrictions to language or publication type, where conference abstracts, journal articles, duplicate publications, and clinical trial protocols were checked. The search criteria was limited to human females. The search was independently conducted by two authors (I.G. and C.D.) and included medical subject heading, subheadings, word variations, and free text; hysterectomy, menorrhagia, ablation, and resection. The full-text articles of the identified studies were screened and assessed for eligibility by title and abstract and then by full text independently by two authors (C.D. and I.G.). The senior author (A.M.) resolved any disparities and crosschecked. The categories of data to be collected were agreed upon and extracted using a standardized method. Two researchers (C.D. and I.G.) were responsible for documenting the data on an excel sheet.

The primary outcomes included subjective patient’s perceived improvement of bleeding symptoms (self-reported), objective reduction of blood loss measured using the pictorial blood loss assessment chart (PBAC), and patient satisfaction. The patient satisfaction was measured using various point Likert scales (e.g., 3, 4, or 5 point) consisting of very satisfied, satisfied, uncertain, dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied. However, due to the variability of this scale, we deemed the patients to either be satisfied or not satisfied. Those who voted as “very satisfied” and “satisfied” were classified as being “satisfied” with the intervention and those who voted as “dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied” were classified as being “not satisfied”. We excluded those who voted in the neutral category “uncertain” from the meta-analysis. The secondary outcomes included self-reported chronic pelvic pain; self-reported short-term and long-term adverse events; quality of life (QoL) measured using a number of scales, such as the short form-12 (SF-12), Euro quality of life-5D (EuroQol-5D), Golombok Rust Inventory of Marital State (GR inventory-score), and hospital anxiety and depression; sexual function measured using the Sabbatsberg sexual rating score (SSRS); need for further surgery or previously carried out at follow-up; duration of surgery; duration of hospital stay; self-reported time to return to work and resume normal activity; and costs of health services.

The data were analyzed using Review Manager (RevMan v.5.2.20; Cochrane Collaboration) [10]. Quantitative synthesis was performed when more than one eligible study was identified. The results were expressed as weighted mean difference with standard deviation for continuous outcomes; and risk-ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous variables using the Mantel-Haenszel method [11]. The statistical heterogeneity was measured using the chi-square test and I2 scores, and the methodological heterogeneity was assessed during the selection. Heterogeneity was classified as low (<25%), moderate (25–75%), and high (>75%). This classification is a consist and standardized way to communicate the degree of statistical heterogeneity in meta-analysis [12]. A funnel plot was conducted for the primary outcome according to the PRISMA checklist, to check for the existence of publication bias and assess heterogeneity. The fixed effects model was used [13]. Sensitivity analysis was performed for the primary outcome, subjective bleeding perception, by excluding the RCTs with unclear quality. GradePRO software (Cochrane Collaboration) was used to assess the quality of evidence (Supplementary Table 2) [14]. The risk of bias was assessed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews [7] and generated through RevMan software (Cochrane Collaboration) [10]. Sensitivity analysis was performed for the primary outcomes by excluding the RCTs having low and/or unclear quality.

Results

Fig. 1 shows the literature search results according to the PRISMA flowchart. After the title and abstract screening, 66 articles were screened by full-text, and 54 were subsequently excluded with reasoning (Supplementary Table 3). The 12 RCTs included 2,028 women (hysterectomy, n=977 vs. (E:A/R), n=1,051; Table 1). Hysterectomy was compared with EA in five studies [15–19], ER in five studies [20–24], and ablation and resection in two studies [25,26]. The EA techniques included microwave [18], thermal balloon [15–17,19], radiofrequency [15], and bipolar [25]. The methods of hysterectomy were abdominal (open or laparoscopic) [15,16,18,19,21,23,24] and vaginal [17,20,22,25,26].

The corresponding authors of the included RCTs were contacted to provide supplementary or missing data, but only two responded [17,25]. The follow-up period in one study was 14 years [24], whereas the follow-up period in all the other RCTs was 1–4 years [15–23,25,26]. One study was a quasi-RCT [18] with women allocated according to the date of admission.

Across all the studies, 435 women (21.45%) were lost to follow-up, where 250 and 185 women were lost to follow-up before 2-year and after 2-year, respectively. The mean age of women undergoing hysterectomy and (E:A/R) was 42.61 and 42.63 years, respectively; their mean body mass index was 27.29 and 27.09 kg/m2, respectively; and their mean parity was 2.40 and 2.25 pregnancies, respectively.

1. Bleeding perception: subjective outcome

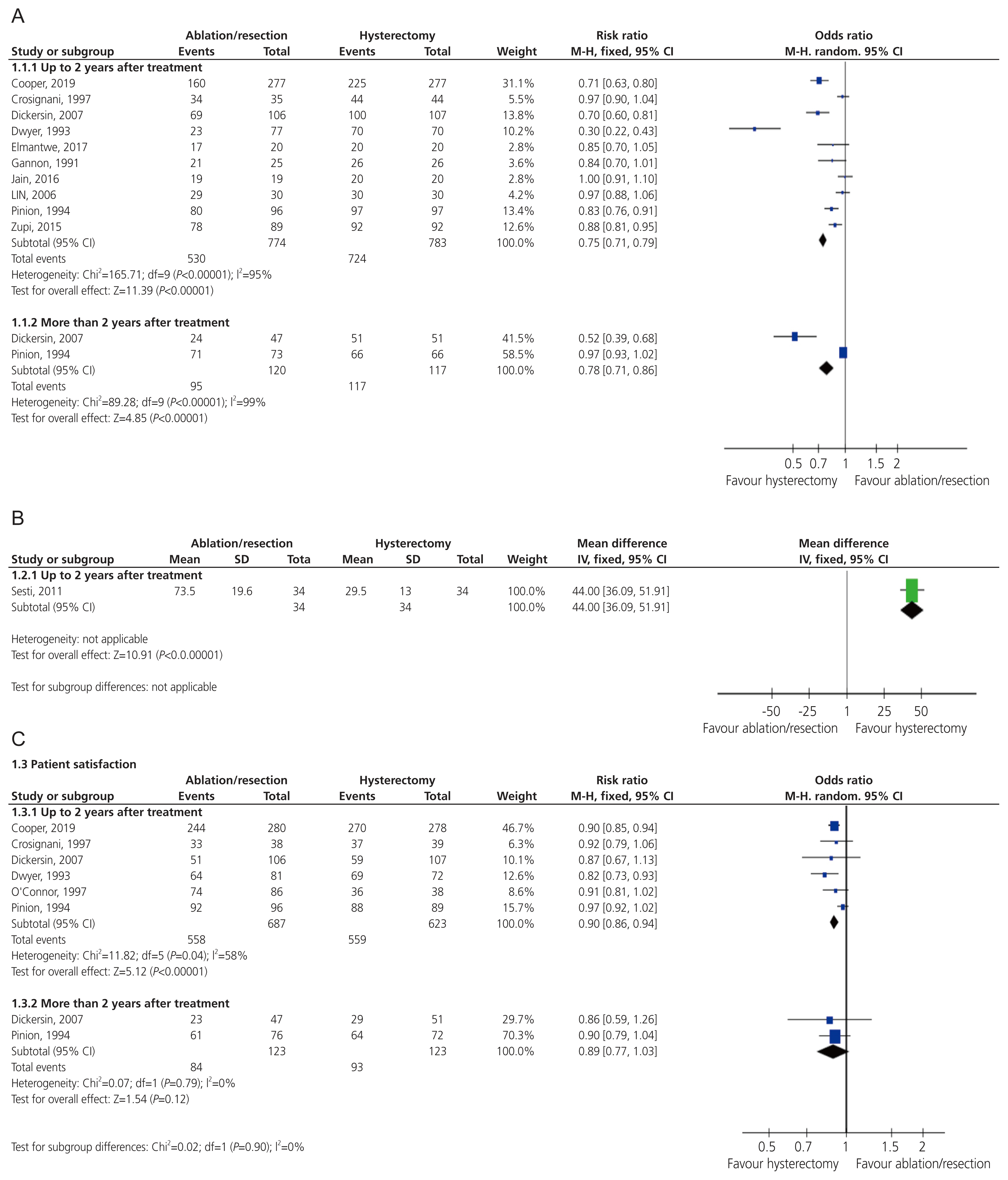

Ten studies [15–18,20,21,23,26] reported that the women’s perception of their bleeding had improved. The meta-analysis revealed that the women who had hysterectomies were more likely to show improvement in the bleeding symptoms compared with those who had (E:A/R) up-to 2 years follow-up (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.71 to 0.79; I2=95%). Similar results were obtained at the follow-up period post 2 years (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.71 to 0.86; I2=99%) (Fig. 2A). These results pertained to the sensitivity analysis including high-quality studies only (Supplementary Fig. 2). The grade quality of evidence for this outcome was low. A funnel plot for this outcome identified an outlier; thus, this study should be examined more closely to determine if the results were legitimate or skewed the overall data (Supplementary Fig. 3).

2. Bleeding perception: objective outcome

Two studies used PBAC score [19,25] however, only one study [19] reported sufficient evidence for analysis. The findings up-to a 2-year follow-up period were in favor of the women in the hysterectomy group compared to those in the (E:A/R) group (mean difference [MD], 44.00; 95% CI, 36.09 to 51.91; Fig. 2B). In the second study [25], it was reported that 60% of the women undergoing resection were amenorrhoeic at the 1 year follow-up, and 25% experienced hypomenorrhea as reflected by the PBAC score. The grade quality of evidence for this outcome was moderate.

3. Patient satisfaction

Six studies recorded patient satisfaction at varying time intervals in the 2 years following treatment [15,16,20,22,23,26]. Two studies reported satisfaction more than 2 years following the procedures [16,26]. Cooper et al. [27] measured the satisfaction using the Likert scale which ranged from totally satisfied to totally dissatisfied. Dickersin et al. [16] rated the satisfaction on a 3-point scale (very satisfied, mixed, and very dissatisfied). Three studies [20,22,26] rated satisfaction on a 5-point scale (very satisfied, satisfied, uncertain, dissatisfied, and very dissatisfied). Due to the variability of reporting satisfaction between the studies, this outcome was examined on a binary scale with patients being categorized as “satisfied” or “not satisfied”. The cohort of patients who voted for “neutral” on the Likert scale were not included in meta-analysis to improve the validity and reliability of the measure.

The patient satisfaction was higher post-hysterectomy when assessed up-to a follow-up period of two years (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.86 to 0.94; I2=58%). However, there was no difference in the satisfaction between the two groups after 2 years (RR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.03; I2=0%). The grade quality of evidence for this outcome was low (Fig. 2C).

4. Chronic pelvic pain

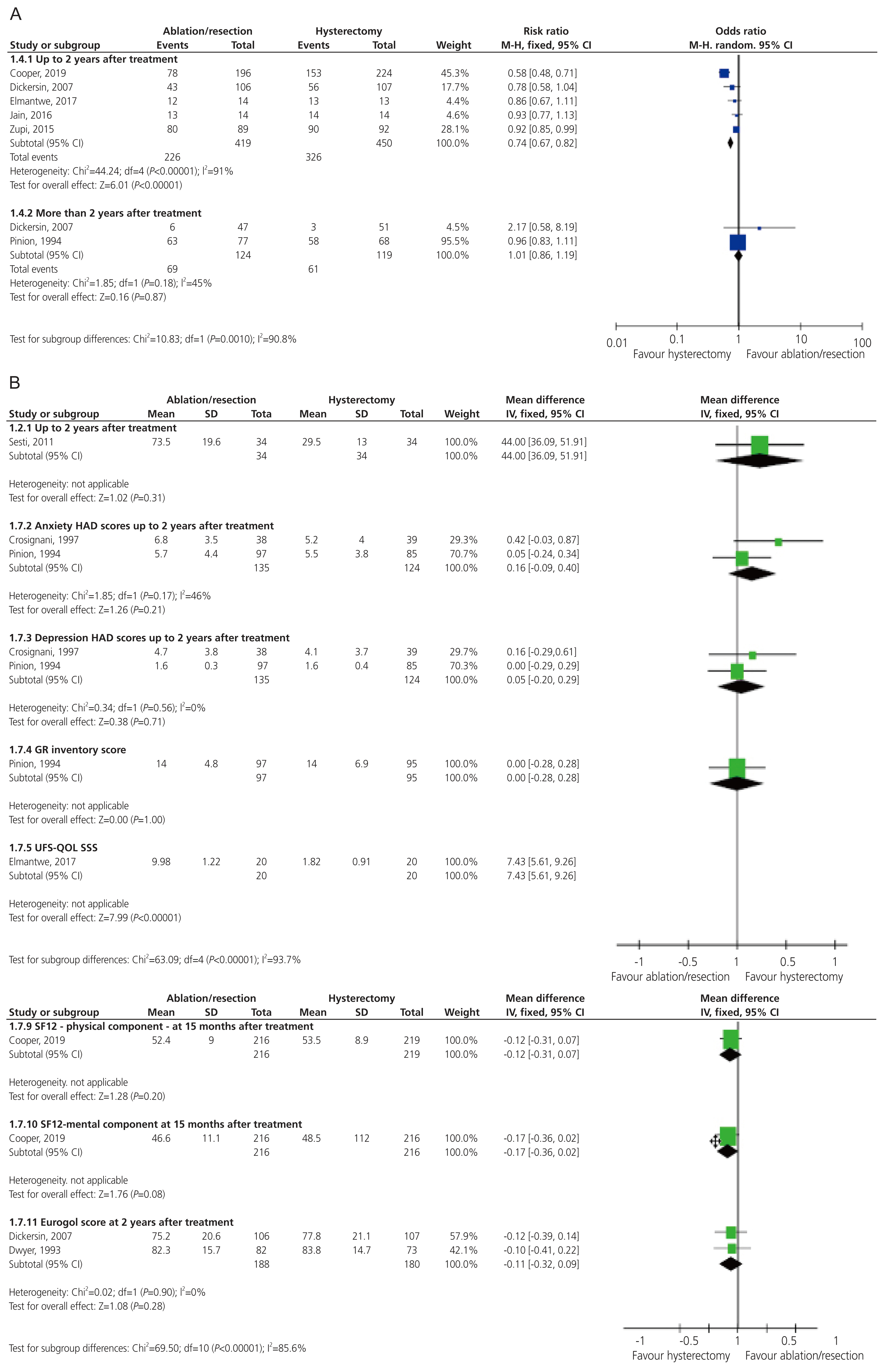

Five studies investigated chronic pelvic pain with a follow-up period of up-to 2 years [15,16,18,24,25]. Two studies assessed chronic pelvic pain after 2 years [16,25]. The meta-analysis revealed that the patients who underwent hysterectomy had a greater chance of having no chronic pelvic pain up-to 2-year after treatment, compared to the patients who underwent (E:A/R) (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.67 to 0.82; I2=91%). However, there was no significant difference in the number of patients who experienced chronic pelvic pain 2 years after (E:A/R) or hysterectomy (RR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.86 to 1.19; I2=45%) (Fig. 3A).

5. Adverse events-short-term

Eight studies reported short-term adverse events [15–17,21–24,26] (Supplementary Fig. 4). The grade quality of evidence for this outcome was moderate.

The outcomes favoring (E:A/R) were sepsis (RR, 0.03; 95% CI, 0.00 to 0.56; one study) [22]; blood transfusion (RR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.07 to 0.59; I2=0%; five studies) [17,22–24,26]; pyrexia (RR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.35; I2=66%; three studies) [16,23,25]; vault hematoma (RR, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.34; I2=0%; five studies) [16,21,23,24,26]; wound hematoma (RR, 0.03; 95% CI, 0.00 to 0.53; one study) [26]; urinary tract infection (RR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.10 to 0.42; I2=0%; four studies) [21,23,24,26]; wound infection (RR, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.28; I2=0%; three studies) [21,23,26]; urinary retention (RR, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.57; I2=0%; two studies) [21,23]; and voiding problems (RR, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.54; one study) [15].

The outcomes favoring hysterectomy were fluid overload (RR, 7.80; 95% CI, 2.16 to 28.16; I2=0%; four studies) [16,22,24,26] and perforation (RR, 5.42; 95% CI, 1.25 to 23.45; I2=0%; four studies) [16,22,23,26].

The outcomes showing no certain difference between both groups were pelvic hematoma (RR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.01 to 3.80; one study) [23]; hemorrhage (RR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.32 to 1.46; I2=35%; three studies) [22,24,26]; anesthetic (RR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.12 to 1.59; I2=0%; two studies) [19,23]; gastro-intestinal obstruction/ileus (RR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.04 to 5.01; one study) [23]; laparotomy (RR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.08 to 1.97; I2=0%; two studies) [21,23]; cystotomy (RR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.01 to 4.42; one study) [14]; cervical laceration (RR, 2.86; 95% CI, 0.47 to 17.40; I2=0%; three studies) [14,19,21]; dilutional hyponatremia (RR, 2.94; 95% CI, 0.12 to 71.3; one study) [20]; pelvic infection (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.34 to 1.58; I2=0%; two studies) [20,23]; and nausea and vomiting (RR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.05 to 5.52; one study) [15].

6. Adverse events-long-term

Ten studies recorded long-term adverse events [6,16–18,20–23,25,26] (Supplementary Fig. 5). The grade quality of evidence for this outcome was very low.

The outcomes favoring endometrial ablation or resection were sepsis (RR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.13 to 0.58; one study) [22]; hematoma (RR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.12 to 0.99; I2=0%; four studies) [6,20,22,23]; voiding dysfunction (RR, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.03 to 0.63; one study) [15]; and pyrexia (RR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.08 to 0.61; one study) [16]. The outcome favoring hysterectomy was recurrent menorrhagia (RR, 2.52; 95% CI, 1.92 to 3.32; I2, 0%, seven studies) [15,17,20,23,25,26].

The outcomes which showed no certain difference between both procedures were hemorrhage (RR, 2.94; 95% CI, 0.12 to 71.30; one study) [20]; wound infection (RR, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.02 to 1.04; I2=0%; two studies) [14,18]; readmission (RR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.17 to 1.28; I2=0%; three studies) [16,20,23]; neuropathy (RR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.01 to 2.93; one study) [16]; thromboembolic event (RR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.01 to 4.42; one study) [16]; cardiorespiratory event (RR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.01 to 2.93; one study) [16]; pneumonia (RR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.01 to 8.68; one study) [16]; endometritis (RR, 3.22; 95% CI, 0.13 to 78.13; one study) [16]; and cuff cellulitis/abscess (RR, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.00 to 1.24; one study) [16].

7. QoL and sexual function

Nine studies examined the QoL using a variety of methods [15–17,19,20,23–26]. SF-12, EuroQol-5D, GR inventory-score, and HAD score showed similar results in both groups. Hysterectomy was favored at 2 years post-treatment (Fig. 3B) by uterine fibroid symptom and quality of life subscale scores (MD, 7.43; 95% CI, 5.61 to 9.26; one study) [25]; social functioning (MD, −0.91; 95% CI, −1.10 to −0.72; I2=93%; four studies) [19,20,23,24]; energy (MD, −0.42; 95% CI, −0.57 to −0.26; I2=91%; five studies) [16,19,20,23,24]; pain (MD, −0.28; 95% CI, −0.44 to −0.13; I2=80%; five studies) [16,19,20,23,24]; general health perception (MD, −0.40; 95% CI, −0.55 to −0.25; I2=75%; five studies) [16,19,20,23,24]; and physical functioning (MD, −0.29; 95% CI, −0.47 to −0.11; I2=89%; four studies) [19,20,23,24].

The remaining subsections of the Standard Form 36; namely role limitation (physical), role limitation (emotional), and mental health, showed no certain difference between the two groups. The sexual function was measured in one study [20] using the SSRS at a 3-year follow-up period, which showed similar results between the two groups (MD, −0.22; 95% CI, −0.67 to 0.23).

8. Further surgery

Further need for surgery was reported in 11 studies [15–17,19–26]. All the studies reported that the women who had undergone (E:A/R), but not those who had undergone hysterectomy, required to undergo a further surgery at the follow-up periods of up-to 2 years (RR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.13 to 0.17; I2=89%) and more than 2 years [22,26] (RR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.36; I2=88%; Fig. 4A). About 15.4% of the women had to undergo further surgery in the first two after the procedure. The percentage increased for the follow-up period of more than 2 years to 28.4%.

(A) Further surgery. (B) Further surgery and duration of hospital stay. (C) Time to return to normal activity and time to return to work. CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; SD, standard deviation; IV, inverse-variance.

The patients in the hysterectomy group were reported to have undergone further surgery in three studies. One study described four incidences of further surgery; one ovarian cyst excision, two oophorectomies, and one cystoscopy [22]. One study reported two laparotomies following hysterectomy but did not specify the surgery type [26]. Another study required cervical stump removal following laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy [15].

The most common causes of further surgery in the patients who underwent (E:A/R) were continued HMB or pain [15,16,20,22,23,26]. One study reported further surgery at a follow-up period of 14 years favoring hysterectomy. It was not included in this meta-analysis as more than 20% of the patients were lost to follow-up in the ablation group [24]. The grade quality of evidence for this outcome was very low.

9. Duration of surgery and hospital stay

Ten studies reported the duration of surgery [15,17,19–26], which was revealed to be shorter in the (E:A/R) group than the hysterectomy group (MD, −25.19; 95% CI, −25.19 to −24.47; I2=97%; Fig. 4B). Nine studies reported the length of hospital stay [15,16,20–26], which was shown to be shorter in the (E:A/R) group than the hysterectomy group (MD, −0.07; 95% CI, −0.07 to −0.07; I2=100%,) (Fig. 4B).

10. Time to return to work and normal activity

The time to return to work was reported in six studies [15,20–24]. This ranged from 2.4 to 9.0 weeks in favor of endometrial ablation or resection compared to hysterectomy (MD, −4.22; 95% CI, −4.31 to −4.14; I2=100%; Fig. 4C). The time to return to normal activity favored (E:A/R) by 5 to 21 days (MD, −10.41; 95% CI, −12.28 to −8.54; I2=97%; Fig. 4C), and was reported in three studies [20,22,23].

11. Cost effectiveness

The costs associated with healthcare were reported in 3 RCTs [21,23,26] spanning a follow-up period of 1–5, 6 years. Two studies [21,24] utilized questionnaires to evaluate the cost of retreatment [23,26], length of hospital stay(s) since the initial treatment [23,26], number of outpatient visits [26], and need for hormone replacement therapy. The unit cost for each resource were determined and added to determine the overall cost of therapy. Gannon et al. [21] did not report how the cost was determined for the two treatment groups. The three studies [21,23,26] reported comparison in the cost between hysterectomy and (E:A/R) with mean costs of GBP1216 and GBP3809, respectively (Table 2). The cost of sanitary products was lower for those who had undergone hysterectomy with savings of GBP85.10 compared to GBP58.30 in the (E:A/R) group [26]. No meta-analysis was conducted for the cost effectiveness as there was no uniform scale or comparable outcome.

12. Risk of bias

The risk of bias was assessed and demonstrated in the risk-of-bias graphs (Fig. 5). The majority of studies had low risk of bias for allocation concealment and random sequence generation. However, one study used a quasi-randomized method [18], which provides high selection bias. Apart from one study [19], all the other studies had high risk of bias for blinding which could either be attributed to the single blinding methods for the assessment of outcomes [16,24] or the lack of blinding of participants, investigators, or assessors [15,17,18,20–23,25,26]. These studies were therefore deemed high risk of performance and detection biases.

13. Heterogeneity

No studies were excluded due to methodological heterogeneity. There was a low estimate of statistical heterogeneity (I2 <25%) in the patient satisfaction in the follow-up period of more than 2 years, further surgery, and majority of adverse outcomes. There was a moderate estimate of statistical heterogeneity (25%; <I2 <75%) in the patient satisfaction in the follow-up period of less than 2 years. There was a high degree of statistical heterogeneity (I2 >75%) in the subjective bleeding, QoL scores, duration of surgery, hospital stay, return to work, and normal activity.

Conclusion

Although hysterectomy and (E:A/R) improved the QoL and were safe surgical options, this review showed that hysterectomy had significantly better results in terms of improving the subjective and objective bleeding-symptoms and patient-satisfaction up-to a follow-up period of 2 years.

In congruence with the 2020 Fergusson review, women who underwent hysterectomy showed greater improvements in bleeding than those who underwent (E:A/R) in the short term. The effect, however, was reduced over time as observed at the 2-year and 4-year follow-up periods which is reflected in the increasing number of re-interventions (15.4% and 28.4%, respectively) [4]. Literature suggests that at 5-year post-EA, 20% of the patients will have undergone hysterectomy [27].

The satisfaction rates at the follow-up period of up-to 2 years were higher for hysterectomy compared to (E:A/R). The literature reported 5% dissatisfaction following hysterectomy compared to 13% following ablation at 12 months [28]. However, the difference in the satisfaction was similar to (E:A/R) at the 2-year follow-up period. This supports the employment of (E:A/R) over hysterectomy as it shows that more conservative procedures can provide similar long-term satisfaction as more radical procedures. The discrepancy between symptom control and satisfaction rates could be explained on psychological grounds. The satisfaction may be attributed to the fulfilment of expectations rather than symptom control [29]. It can be concluded that it is vital to address the patient’s expectations prior to carrying out the procedure [30].

A study by Brandsborg et al. [31] showed that, after hysterectomy, 31.9% of the women experience chronic pelvic pain with a significantly increasing risk if they had pelvic pain pre-operatively. Talukdar et al. [32] and Thomassee et al. [33] revealed that 16–20.8% of the women who undergo EA experience pelvic pain, mostly in the first 2 years [32,33]. Our results suggest that there is no significant difference between the groups after 2 years.

The meta-analysis showed overall low incidences of adverse events following all procedures. Several studies reported that women experienced more postoperative complications following hysterectomy than those who received (E:A/R) [34–36].

The QoL was measured using various scales. Therefore, combining scales was not possible as aspects were measured using different domains. Our data showed that in some QoL measures, hysterectomy provided more substantial improvement, whereas the results were similar between the groups in other domains. Literature supports that hysterectomy could result in the improvement of sexual function and QoL [37]. However, no significant difference was evident in the sexual function of the patients in the two groups in the RCTs analyzed in this review [20].

Our results showed that the duration of surgery and hospital stay increased post-hysterectomy compared to (E:A/R). These findings are consistent across the trials and conform with a previous meta-analysis which concluded that the patients undergoing hysterectomy were likely to experience increased hospital stay [4,28]. It is important to note that the duration of surgery and hospital stay for hysterectomy is becoming shorter with the advancement of the surgical techniques. More recent studies report a preference for laparoscopic hysterectomies compared to abdominal or vaginal hysterectomies [38]. However, hysterectomy remains a major procedure, with longer duration of surgery and hospital stay, compared to (E:A/R).

The time to return to work and resume normal activity was shorter in the patients undergoing (E:A/R). This could be attributed to the fact that EA does not require surgical incisions. Furthermore, the techniques are simple to learn and perform thus the procedure allows for the rapid recovery and early return to work [39]. The cultural norms may influence the time to return to work since the trials occurred in various countries. The physical work demands might also influence evidence [40].

Multiple factors affect the cost effectiveness of (E:A/R) compared to hysterectomy. One modelling study suggested that a second-generation ablation technique, namely the global endometrial ablation, provides more savings as it involves fewer complications and shorter hospitalization [41]. Similar findings were reported by Gannon et al. [21] who demonstrated significantly lower cost and shorter hospitalization for EA. A model-based evaluation showed that hysterectomy was more cost-efficient as it provides more quality-adjusted life years compared to the first- and second-generation techniques [5]. Moreover, Sculpher et al. [42] provided evidence showing that hysterectomy was more cost-effective, despite not being strongly conclusive. A follow-up from the Pinion et al. [26] cohort demonstrated that the costs of EA were 7% lower than those of hysterectomy [43]. Overall, hysterectomy is more expensive but might be more cost-effective over time due to the less need for a repeated operation or further care. For instance, in the studies which included a follow-up period of 1–2.2 years [21,23], the cost difference between the groups was greater compared to the study with a follow-up period of 4–5.6 years [44,45]. Despite the limited data, there is a significant difference showing that the costs decreased with the increase in the follow-up period. Thus, further research is needed to address this issue.

The completion of data sets and high-quality RCTs are essential in a quality systematic review. The majority of these RCTs (75%; 9/12 RCTs) had good sequence generation and allocation concealment compared with the reported literature which showed that only 25% of the RCTs report the randomization process [46].

Our study has some limitations. The lack of blinding in the included RCTs could pose a source of bias [47]. Hall et al. [46] showed that 50% of the surgical RCTs report blinding procedures. Blinding of assessors was also low (25%; 3/12 RCTs); these findings were lower than those reported in literature. Incomplete outcome data can also pose a source of attrition bias. Surgical trials commonly have attrition bias, especially with mid- to long-term follow-up periods [48].

High levels of heterogeneity pose another potential limitation due to the differences in how procedures were performed between the different RCTs. Accordingly, sensitivity analysis was performed to exclude the low-quality studies. To address the statistical heterogeneity among the studies, we re-checked the data extraction and entry into RevMan. In addition, we conducted subgroup analysis to explore the heterogeneity (up-to and more than 2 years after treatment). Finally, the follow-up duration poses a potential limitation. Thus, we intend to update this review within 2–3 years to capture the longer-term outcomes.

This meta-analysis shows that (E:A/R) offers alternatives to hysterectomy. Both procedures have high effectiveness rates, impact on QoL, and safety. Hysterectomy is associated with greater improvement in the bleeding symptoms, both subjectively and objectively, and higher patient-satisfaction up-to 2 years. However, it has longer operating times, longer recovery periods, and higher rates of postoperative complications. On the other hand, (E:A/R) has lower initial cost than hysterectomy but the need for further surgery is common; therefore, there is no difference in the costs in the long-follow-up. These results should be interpreted with caution due to the heterogeneity of the trials included. An adequately-powered and carefully-planned non-inferiority RCT comparing between the different methods of (E:A/R) to those of hysterectomy with long term follow-up periods is required to inform the surgeons, patients, and decision makers with the most clinically-effective and cost-effective surgical treatment for HMB.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participating authors for enabling this study to be completed. We would also like to thank Dr. David Cooper MSc, PhD for kindly reviewing the meta-analysis statistics.

Notes

Ethical approval

No ethical approval is needed to run this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Patient consent

No patient consent is needed to run this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and did not receive any funding for this study.

Funding information

No fund was provided.