Prenatal diagnosis of fetal adrenal hemorrhage and endocrinologic evaluation

Article information

Abstract

We present a case of a fetal adrenal hemorrhage, a rare disease in fetal life, detected prenatally at 36 weeks' gestation by ultrasound. Routine ultrasound examination at 36 weeks' gestation by primary obstetrician showed a cyst on the fetal suprarenal area. Initially, the suspected diagnosis was a fetal adrenal hemorrhage, but we should diagnose differently from neuroblastoma. Subsequent ultrasound examination at 38 and 39 weeks' gestation showed increase of the cyst in size. A 3.34-kg-male neonate was born by spontaneous vaginal delivery at 39 weeks' gestation. The diagnosis of adrenal hemorrhage was confirmed by postnatal follow-up sonograms and magnetic resonance imaging. Course and sonographic signs were typical for adrenal hemorrhage and the neonate was therefore managed without surgical exploration.

Introduction

Adrenal hemorrhage is generally diagnosed by sonography during the newborn period but is rarely detected in uterus. The prenatal diagnosis has not been clearly described and its sonographic appearance can be confused with that of several other pathologic conditions [1]. Abdominal sonography has greatly facilitated the diagnosis of adrenal hemorrhage particularly when the clinical presentation is subtle [2]. We present a case of prenatal adrenal hemorrhage initially detected by ultrasound as an echogenic mass at the suprarenal area.

Case report

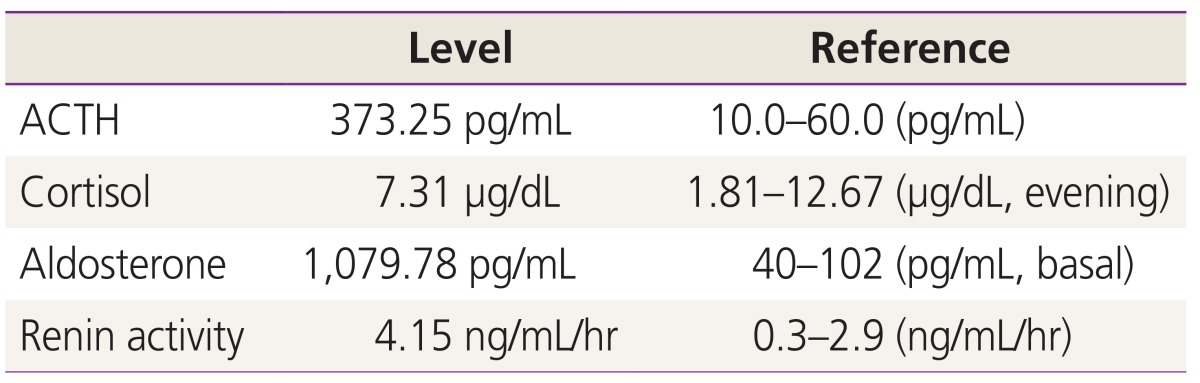

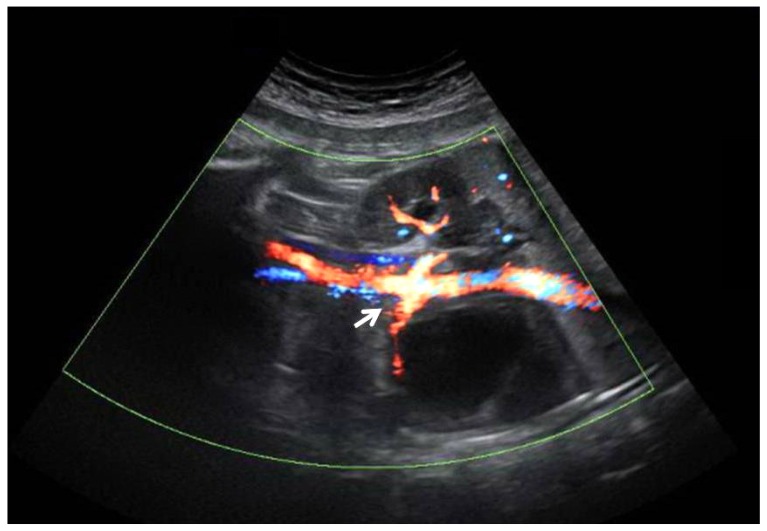

A 32-year-old gravida 2, para 1 woman was referred to our obstetrics center at 38 weeks of gestation because of a suspected suprarenal cystic mass. Her previous medical history was unremarkable, and she had no family history of congenital malformation. On detailed fetal sonography, a solitary cystic mass located superior to the left kidney measured 33×31×28 mm was found. Two-dimensional and three-dimensional ultrasound clearly demonstrated that the tumor was arising from the adrenal gland. Biophysical profile, fetal biometry and Doppler examinations of the umbilical cord were normal. The size of the mass increased to 40×36×34 mm at 39 weeks' gestation (Fig. 1). At 39 weeks' gestation, the mother was delivered of a healthy male neonate weighing 3.34 kg. No anemia or palpable abdominal mass were found in the neonate. The umbilical cord blood sampling was done at the delivery to check the fetal endocrinologic function (Table 1). The adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and aldosterone levels were 373.25 pg/mL and 1,079 pg/mL respectively and these figures were beyond the normal range. But there were no definite abnormal clinical findings on the neonate. The postnatal sonography on the day of birth demonstrated a 40×38×33 mm cystic mass at the upper pole of the left kidney. The perfusion inside the mass was not detected by the color-coded Doppler sonography nor by the power Doppler sonography. Tumor markers, including urinary vanillylmandelic acid, urinary homovanillic acid were within normal ranges. A T2 weighted imaging of magnetic resonance imaging showed a well-demarcated suprarenal mass arising from left adrenal gland. As the findings were suspicious of an adrenal hemorrhage, invasive examinations as well as computerized tomography and 131 I-labelled meta-iodobenzylguanidine scans were unnecessary.

Prenatal Power Doppler imaging at 39 weeks of gestational age showed an anechoic suprarenal cystic mass above the renal artery (white arrow). No flow can be seen whithin the mass.

Discussion

Prenatal ultrasound should be able to differentiate abdominal masses from suprarenal masses in most cases. The main differential diagnoses of suprarenal masses are congenital neuroblastoma, lung sequestrations, adrenal hemorrhage, mesoblastic nephroma and duplications of the urinaryor intestinal tract [1]. The most important lesion to excluded is neuroblastoma.

Adrenal hemorrhage was first described by Spencer in 1892 in stillborn infants [3]. Adrenal hemorrhage are not uncommon in newborns, but they may also occur before birth [456]. The incidence of adrenal hemorrhages based on extensive necropsy has been estimated as about 1.7 per 1,000 births [7]. The detection rate in utero is much lower. Although the adrenal hemorrhage occurred on the left side in our case, adrenal hemorrhage affects the right side two to three times more frequently than the left side and is bilateral in 5% to 15% of cases [28].

Adrenal hemorrhages may be entirely echogenic, mixed echogenic, or echolucent when first imaged. Active adrenal bleeding appears sonolucent. Later on, a solid clot with diffuse echogenicity is found, retracting continuously. Finally, as liquefaction occurs, the mass demonstrates mixed echogenicity, and eventually becomes completely anechoic [910]. The diagnosis of an adrenal hemorrhage has been made when an echolucent mass was found and then disappeared on follow-up ultrasound studies [411]. Our case was different in that the clinical manifestation was a persistent homogenous echogenic adrenal mass without any resolution during serial ultrasonographic scanning for more than 3 weeks. The mass, posterior to the stomach, was first found incidentally during the 36 weeks' gestation when the first time adrenal hemorrhage occurred. The extension of the lesion was scanned using ultrasound at 38 weeks' gestation. The whole clinical course of our case reminded us that all of the pictures we found were during the initial stage of the adrenal hemorrhage.

Adrenal insufficiency is found very rarely even in cases with severe bilateral adrenal hemorrhage. Residually functioning adrenal tissue in the subcapsular region is left in most cases and adrenal insufficiency only manifests clinically when more than 90% of each gland are destroyed [2]. In this case, we performed endocrinologic studies with cord blood collected from the umbilical vein right after delivery, and we could identify the elevation in the values of ACTH, aldosterone, and rennin activity. Cases where endocrinologic evaluation of umbilical cord serum had been confirmed is rarely found in the previous literature. Elevated values of ACTH, aldosterone, and renin activity does not imply adrenal insufficiency clinically, but it is considered as changes followed by compensative reactions. Therefore, as adrenal hemorrhage resolves by spontaneous remission, verifying the recovery of endocrinologic laboratory data to the normal ranges should be done during the observational period after the delivery.

As stated above, it is important that fetal adrenal hemorrhage should be differentiated from congenital neuroblastoma. Congenital neuroblastoma is the most frequent suprarenal malignancy, with an incidence of approximately 6 out of 1,000 liveborns [12] and a diverse sonographic appearance. Ultrasonography and color-coded Doppler sonography are useful in differentiating an adrenal hemorrhage from a congenital neuroblastoma. The neuroblastoma often shows a network of microscopic vessels with characteristic high-velocity Doppler shifts inside the tumor and stippled calcifications [13]. In contrast, adrenal hemorrhage shows the peripheral rimlike calcifications and no blood flow can be seen within the mass with power Doppler examination. It has been suggested that many of the neonatal cases of neuroblastoma can regress spontaneously. Yamamoto et al. [14] found tumour regression in 11 of 12 cases of early stage neuroblastoma detected by mass screening. Therefore, recommendations for treatment of suprarenal masses, discovered incidentally during fetal life, have changed in recent years. Surgical exploration in every case gave way to a wait-and-see attitude based on close prenatal and postnatal ultrasound follow-up. How long to observe a suprarenal cystic lesion and when to resort to surgical intervention remain controversial. Appropriate prenatal assessment and close sonographic monitoring may avoid surgery in cases of benign masses like adrenal hemorrhage or spontaneously regressing neuroblastomas.

Notes

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.