Minimally invasive surgery for deep endometriosis

Article information

Abstract

Deep endometriosis (DE) is endometriotic tissue that invades the peritoneum by >5 mm. Surgery is the treatment of choice for symptomatic DE, and laparoscopic surgery is preferred over laparotomy due to better vision and postoperative pain. In this review, we aimed to collect and summarize recent literature on DE surgery and share laparoscopic procedures for rectovaginal and bowel endometriosis.

Introduction

Endometriosis affects approximately 6.0–10.0% of reproductive-aged women, causing pelvic pain in 50.0–60.0% and infertility in 50.0% [1–3]. Endometriosis was diagnosed in 1.0–7.0% of Korean women undergoing gynecologic surgery, 3.0–9.0% of those undergoing surgery for chronic pelvic pain, and 3.0–45.0% of those with infertility [4].

Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus [5,6]. It can manifest as superficial peritoneal lesions, endometriomas, deep endometriotic nodules with scarring and adhesions, and non-pelvic lesions [5]. Retrograde menstruation of estrogen-sensitive endometrial cells and tissues results in inflammatory response and peritoneal disease [1].

Deep endometriosis (DE) is defined as endometriotic tissue infiltrating the peritoneum by >5 mm [7–9]. These lesions can be found in the uterosacral ligament, bowel, bladder, ureter, vagina, parametrium, and the diaphragm [8,10]. DE is accompanied by severe pain in >95.0% of patients and is likely a contributing factor to infertility [7]. The estimated prevalence ranges between 1.0% and 2.0% [7].

DE can be treated medically; however, most patients need comprehensive surgical excision to relieve symptoms and improve their quality of life (QOL) [11]. Effective deep endometrial surgery requires a comprehensive approach and competence. Laparoscopy is preferred over laparotomy for endometriosis surgery because it provides better visualization of pelvic structures, reduced postoperative pain, blood loss, and recovery time [4,8,12,13].

In this review, we aimed to collect and summarize data from recent literature on DE surgery and share the laparoscopic procedure for rectovaginal and bowel endometriosis.

Methods

We searched PubMed and Google Scholar databases for studies published in June 2023 using the following keywords: “deep endometriosis”, “bowel endometriosis”, “laparoscopy”, and “minimally invasive surgery”. Studies were selected and reviewed if they were published in English. All types of research were included, including randomized controlled trials (RCT), retrospective studies, meta-analyses, and consensus guidelines.

Results

Table 1 shows the current guidelines for DE surgery [7,8,14] and Table 2 summarizes previous RCT and systematic reviews [15–21].

1. Diagnosis of DE

DE should be suspected in women with severe dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, and dyschezia [7]. Before surgery, clinical examination, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can diagnose DE. The sensitivity and specificity of transvaginal ultrasound for detecting DE in the rectosigmoid were 91.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 85.0–94.0%) and 97.0% (95% CI, 95.0–98.0%), respectively, according to a meta-analysis [22]. Another review study reported lower transvaginal ultrasound sensitivity and specificity (79.0% and 94.0%, respectively) than MRI (92.0% and 96.0%, respectively) [23].

2. Patient selection for surgery

Pain and infertility are indications for DE surgery. Surgical excision or ablation should be avoided for incidental findings of asymptomatic endometriosis at the time of surgery, according to the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology guidelines [14]. DE detected using ultrasonography alone without clinical symptoms should not be surgically treated [7]. Resection, leaving free margins on all sides, is the treatment of choice for symptomatic DE [12]. Whenever possible, laparoscopic surgery should be preferred over laparotomy [13]. In severe cases of endometriosis, surgeons should consider restricting surgical excision and referring the patient to an endometriosis specialist [13]. Definitive primary surgical intervention has the most significant advantages [24].

3. Five steps for rectovaginal endometriosis surgery

1) Ovariolysis and temporary ovariopexy

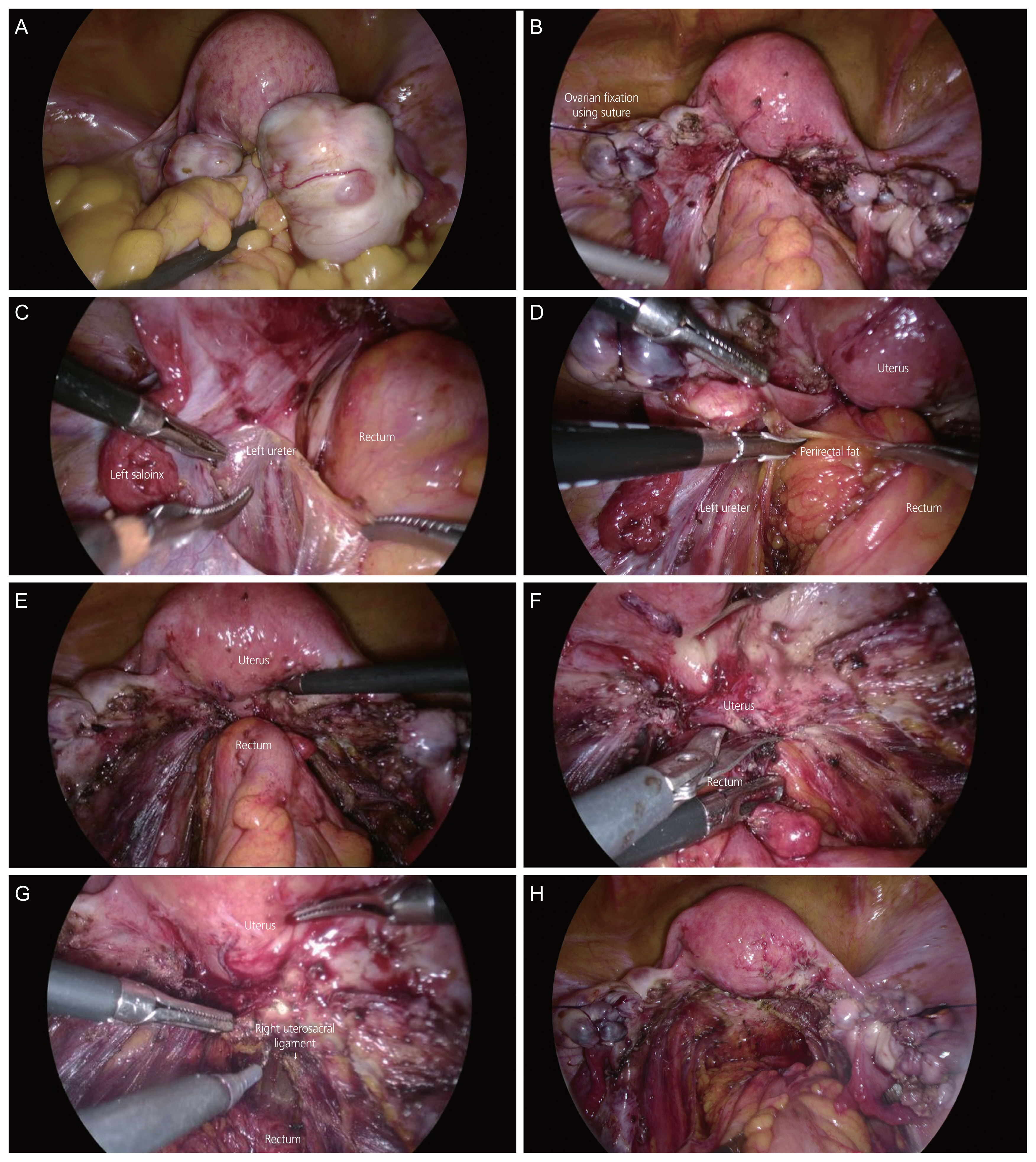

Fig. 1 shows the surgical procedure for deep endometriosis. It is necessary to mobilize the ovaries that adhere to the pelvic sidewall to enhance the visual field during surgery. If endometrioma is present, drainage and cystectomy may precede [8]. Suspension of the ovaries by suturing the anterior pelvic wall can optimize the exposure to the pelvic structures.

Surgical procedure for deep endometriosis. (A) Both endometrioma and cul-de-sac obliteration were seen. (B) Bilateral ovarian cystectomy and ovariopexy were performed. (C) The ureter was identified. (D) The rectum was mobilized by opening pararectal space. (E) Both lateral sides of the rectum were freed. (F) The anterior rectum was separated from the uterus by cold scissors. (G) The endometriotic nodule in the uterosacral ligament was removed. (H) Postoperative image.

2) Identification and dissection of the ureter

Ureterolysis should be performed starting from the level of the upper infundibulopelvic ligament and progressing downward to the level of the uterine vessels to prevent ureteral injury [8].

3) Mobilization of the sigmoid colon and rectum

It is essential to identify the cleavage plane between the bowel and pelvic sidewall, starting from the pelvic brim to expose the left pararectal space and ovarian fossa [7,8]. The opening of the pararectal space should be initiated in healthy tissue [8]. Dissection was continued until the healthy rectovaginal space was opened, and both lateral sides of the rectum were freed [8]. Hypogastric nerve identification is necessary during the procedure to preserve bowel, bladder, and sexual functions.

4) Separation of the anterior rectum from the vagina

This procedure can be performed using cold scissors, blunt dissection, or thermal instruments with minimal collateral thermal spread [8]. An end-to-end anastomotic dilator was inserted in the rectum when necessary.

5) Peritonectomy

After dissection of the rectovaginal space, the endometriotic nodules in the uterosacral ligaments and pelvic peritoneum were removed. The vagina was opened during the procedure, and the defect was closed with sutures.

4. Surgery for bowel endometriosis

1) Shaving

Shaving is not merely a superficial surgical treatment for rectovaginal DE, shaving involves the excision of the DE nodule. This procedure may accidentally open the bowel lumen, requiring a bowel suture [16]. Previous studies reported 1.7% bowel perforation after shaving [16,25–33]. After shaving and nodule removal, the integrity of the bowel wall should be evaluated. If a defect involving the muscularis or partial thickness of the tissue is identified, it can be sutured in one layer using absorbable stitches starting at the healthy margins [8].

2) Discoid excision

If deep endometriotic implants remain after shaving, the rectal wall appears hollow, rigid, and thickened when palpated using a laparoscopic probe [8]. Under such circumstances, full-thickness discoid excision can be performed to complete the excision. Following this, the defect was immediately sutured and closed in two layers to keep the duration of bowel opening as short as possible [7]. Massive irrigation of the pelvis and upper abdomen may be necessary to reduce the risk of postoperative pelvic abscess. Instead of suturing the defect, discoid excision can be performed using transanal staplers, preventing bowel opening into the pelvis [7,8,16].

3) Segmental resection

This is necessary for advanced stages of rectovaginal DE, where extensive infiltration causes irreducible distortion and stenosis of the bowel [16]. During histological evaluation, endometriosis was not found in up to 14.0% of bowel resections [7]. Endometriotic nodules were found outside the muscularis in 12.0% of patients, resulting in 26.0% of unnecessary bowel resections [34]. Therefore, some authors have suggested that the decision to perform bowel resection should not be made before surgery, unless the sigmoid colon shows signs of extensive occlusion [7]. Segmental resection requires mobilizing the rectum at least 20 mm below the rectal nodule to achieve a healthy margin [8,16]. Colorectal anastomosis was performed using transanal staplers after extracting the rectum through an abdominal wall or a vaginal incision [16]. Precautions must be taken to avoid tension in the anastomosis [8]. Several studies have demonstrated the safety and feasibility of intraoperative fluorescence imaging for evaluating anastomotic blood flow, which potentially affects the occurrence of anastomotic leaks [35–37]. Temporary diverting stomas diminish the likelihood of fecal peritonitis fistulas in cases with simultaneous rectal and vaginal sutures or severe endometriosis. The option of a temporary diverting stoma may be considered because it reduces the risk of fistula formation with fecal peritonitis [8].

4) Comparisons of shaving, discoid excision, and segmental resection

There is debate about whether shaving, discoid excision, or segmental resection with anastomosis is best for colorectal endometriosis [14]. Only one RCT compared conservative surgery (shaving and/or discoid excision) with segmental resection [18]. Conservative surgery and segmental resection for DE had similar functional gastrointestinal and urine results [18]. However, the RCT included only large infiltrations of the rectum >20 mm long, involving at least the muscular layer in depth and up to 50.0% of the rectal circumference [18]. Overall postoperative complications of bowel resection for DE were 18.5–22.2%, with 6.4% of patients experiencing major complications, including leakage, fistula, and severe obstruction [15,19]. A recent meta-analysis found no difference in rectovaginal fistulas and leakage between disc excision and segmental colorectal resection [20]. Shaving caused fewer rectovaginal fistulae and leakage than discoid excision [20]. Endometriotic recurrence was considerably lower with segmental resection and discoid excision than with rectal shaving [38].

5. Nerve-sparing surgery

Current guidelines recommend nerve-sparing laparoscopy to treat DE [8,14]. Nerve-sparing surgery effectively reduces the incidence of bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunction without compromising surgical efficacy [10]. A meta-analysis of four RCTs showed that the nerve-sparing technique reduced the risk of persistent urinary retention due to iatrogenic injury to the pelvic autonomic nerves compared to the conventional technique [39]. 1) The presacral space can be opened to identify and skeletonize the inferior mesenteric plexus, superior hypogastric plexus, and hypogastric nerves. During this process, it is important to ensure that the fibers are positioned laterally and dorsally, close to the sacrum, and away from the mesorectal plane to be resected [10,40]. 2) Dissection of the parametrial planes was performed laterally and caudally along the lower hypogastric nerves and proximal part of the inferior hypogastric plexus or pelvic plexus. 3) When endometriosis affects the posterolateral parametrium, a posterior parametrectomy may be performed while preserving the parasympathetic pelvic splanchnic nerves and the cranial and middle parts of the mixed inferior hypogastric plexus. And 4) dissection in the laterocaudal direction beneath the base of each uterosacral ligament was performed by pushing and maintaining the isolated and dissected fibers laterally and caudally to preserve the caudal part of the inferior hypogastric plexus.

6. Outcomes regarding pain and fertility of DE surgery

1) Pain

A systematic review indicated that surgery for DE improves health-related QOL, with bodily pain improving the most [41]. The largest multicenter prospective study reported significant reductions in pelvic pain, urinary and bowel symptoms, and improvements in QOL 6 months after DE surgery [42]. Except for voiding difficulty, these benefits lasted 2 years [42]. The data showed that surgery improved pain and QOL in patients with DE [14].

2) Fertility

DE surgery focuses on pain relief rather than infertility. Therefore, only a few surgical studies on DE have revealed postoperative pregnancy rates of 37.0% [43]. Few randomized studies have evaluated how surgery affects reproductive outcomes of assisted reproductive technology (ART) [14]. A prospective cohort study allowed women with DE to choose surgery before ART or ART directly and found that surgery followed by ART increased pregnancy rates [44].

Conclusion

Herein, we discuss the surgical techniques for DE based on a literature review. Minimally invasive surgery is the treatment of choice in patients with symptomatic deep endometriosis. Surgery is not recommended for incidental symptomless endometriotic lesions. Surgery for severe endometriosis improves pain and QOL in patients, but fertility outcomes remain limited. Therefore, surgery should aim to eradicate all lesions completely. We introduced a laparoscopic approach for safe and effective access to DE and reviewed bowel endometriosis procedures. Patients should be adequately informed about the recurrence and complication rates of each surgical approach before undergoing the procedure.

Notes

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

Waived due to literature review.

Patient consent

Waived due to literature review.

Funding information

None.