Adherence to the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology guidelines: an observational study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The 2012 American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) guidelines were developed to provide guidance regarding cervical pathology and to minimize overtreatment of lesions that may resolve spontaneously. We aimed to evaluate the adherence to these guidelines with referrals for colposcopy at a large academic center and to understand the factors associated with incorrect referrals.

Methods

This retrospective observational study involved women referred to the Virginia Commonwealth University for colposcopy or loop electrosurgical excision procedure from January 2015 to December 2016.

Results

Referral requests from 430 women were reviewed. Among these, 17.4% were discordant with the ASCCP guidelines. The most common discordant colposcopy referrals were low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (48%) and atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (29%). The possibility of incorrect referrals was decreased among high-grade lesions (odds ratio [OR], 0.03), while it was increased in women aged <25 years (OR, 31.6) and in those referred by family medicine (OR, 3.6) or internal medicine (OR, 4.4). Ten patients were referred for cervical cytology results of samples collected from the vaginal cuffs despite hysterectomies performed for benign lesions.

Conclusion

Patients referred outside of the guidelines were most often women aged <25 years with low-grade lesions. Referrals outside evidence-based guidelines may lead to unnecessary procedures and additional healthcare expenses. Our results help identify the areas for provider education and potential areas of concern regarding the implementation of the 2019 ASCCP guideline updates.

Introduction

Cervical cancer screening and colposcopy have played an integral role in reducing the prevalence of cervical cancer over the past 40 years [1]. The guidelines for cervical cancer screening and colposcopy were established more than 15 years ago by the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) and modified over the years with broader understanding of cervical cancer screening [2]. While all women are at risk for cervical cancer, women aged over 30 years are at a greater risk [1]. Furthermore, the majority of the human papillomavirus (HPV) infections in women aged below 24 years resolve spontaneously within 1 to 3 years [3]. The 2012 ASCCP guidelines were developed to identify cervical pathology and to minimize overtreatment of lesions that may resolve spontaneously. Colposcopy and loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) allow the identification and treatment of pre-invasive lesions and aid in the detection of invasive cervical lesions in the early phase when treatment is more effective [4]. Unnecessary colposcopy procedures may result in increased costs, unnecessary treatment, and serious psychological consequences for women [5]. Additionally, the 2019 ASCCP guidelines have transitioned from result-based algorithms to risk-based ones [6].

Several studies have evaluated the adherence of healthcare providers to the 2012 ASCCP guidelines in terms of correct screening intervals and knowledge of HPV co-testing [7,8]. According to Teoh et al. [7], 15% of the providers were unaware of the 2012 guideline changes. However, this study did not report the adherence to guidelines with respect to abnormal cytology results for colposcopy. We aimed to specifically evaluate how providers interpreted the results of the screening tests according to the relevant ASCCP guidelines and to demonstrate the gap in the providers’ knowledge and practice patterns despite evidence-based guidelines that optimize patient management.

The Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology conducts diagnostic procedures such as colposcopy for referred patients. The gynecologists trained faculty physicians at the VCU review all referrals and make recommendations for subsequent care based on the referred cytology and HPV results. The objective of this study was to evaluate the patient referrals for colposcopy by outside physicians to a large academic center and the post-colposcopy recommendations by the physicians from this large center in terms of adherence to the 2012 ASCCP guidelines. We also aimed to identify the factors associated with referrals that did not adhere to the 2012 ASCCP guidelines. An understanding of the factors associated with incorrect referrals due to non-adherence to the 2012 ASCCP guidelines would allow the identification of potential areas of concern in the implementation of the 2019 ASCCP guideline updates.

Materials and methods

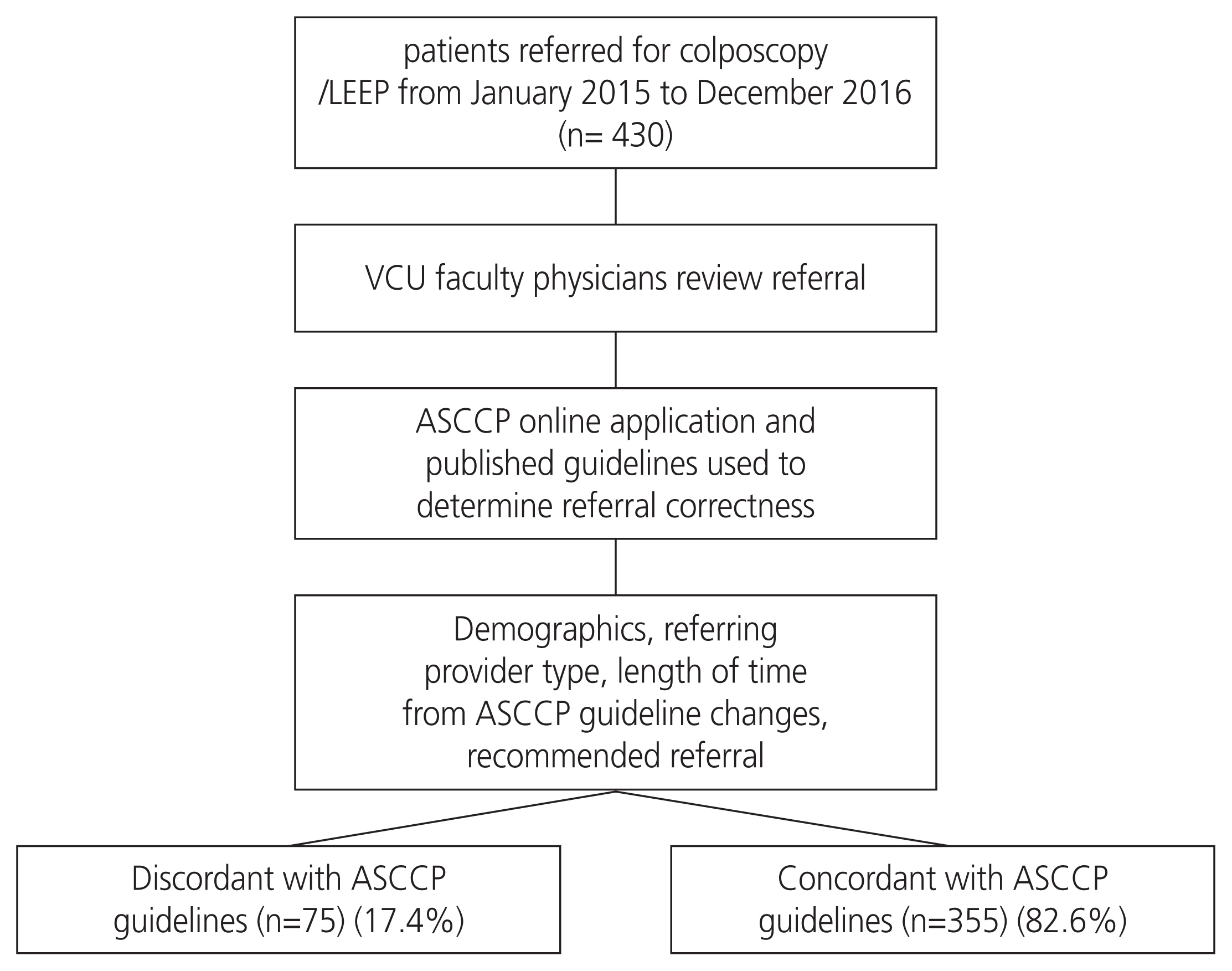

This retrospective study evaluated women referred to the VCU for colposcopy or LEEP from January 2015 to December 2016. Electronic health records of 430 patients referred to the VCU clinic were reviewed to record patient demographics, cervical cytology, HPV status, previous cervical dysplasia, type of referral provider, patient show rate, the duration from the publication of the ASCCP guidelines to the date of receiving the referral, and the recommended intervention. Except in specific clinical scenarios, Pap tests are not recommended until the age of 21 years and many women stop receiving screening for cervical cancer after the age of 65 years. Therefore, patients aged below 21 years and above 65 years were excluded from the study. The final study population comprised of 430 patients. On March 3, 2018, the Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB HM2004659) as exempt, as the study reviewed already existing information and posed minimal/no risk to the subjects. Fig. 1 depicts the methodological process. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Flow Diagram of the descriptive study involving women referred to the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) for colposcopy or loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) online application and published guidelines were used to determine the accuracy of referrals.

1. Study variables

The ASCCP online application as well as the published updated guidelines were used to determine whether the patients were referred correctly and whether correct recommendations were made subsequently by the receiving VCU gynecology provider [2]. The primary outcome was the concordance of the referrals with the guidelines. The secondary outcome variable of interest was whether the receiving VCU gynecology provider made the correct post-colposcopy recommendations that were concordant with the guidelines. The main explanatory variables were cervical cytology results following the Pap test, which were categorical in nature (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance [ASCUS]; atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion [ASC-H]; low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion [LSIL]; high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion [HSIL]; atypical glandular cells [AGCs]; and negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy [NILM]). Other variables representing adherence to the guidelines included the procedures recommended by the VCU provider (colposcopy, LEEP, or re-screening) and HPV test results. Other covariates included patients’ race/ethnicity, age, type of referral provider (gynecologist, family medicine, internal medicine, health departments, veteran affairs, others), history of cervical dysplasia, and whether the patient was examined at the VCU clinic. A variable representing the duration from the publication of the ASCCP guidelines to the date of receiving the referral was included to control for the effect of duration from the implementation of the guidelines to referral to the VCU clinic. A greater duration was anticipated to result in fewer discordant referrals. Due to the small sample size and unbalanced frequencies within the variable categories, some variable categories were combined or not included in the adjusted model. In many patients, the variables for HPV results and previous colposcopy were categorized as not applicable possibly due to the age recommendations for HPV testing and colposcopy. Therefore, these variables were not included in the multivariable logistic regression. According to the 2012 ASCCP guidelines, the preferred protocol for LSIL with negative HPV test is to repeat the test in 1 year. However immediate colposcopy is also acceptable. In the present study, a referral was considered discordant if the cytology result was LSIL and the HPV test was negative.

2. Statistics

Cross tabulations were used to estimate the frequency and percentage of the categories of all study variables. Chi-squared tests were used to determine the statistical significance of the differences in the distribution of these variables between the concordant and discordant referrals. Chisquared statistical analysis was used to estimate the statistical significance of the differences in cervical cytology results by age group for the covariates among the discordant referrals by cervical cytology and age.

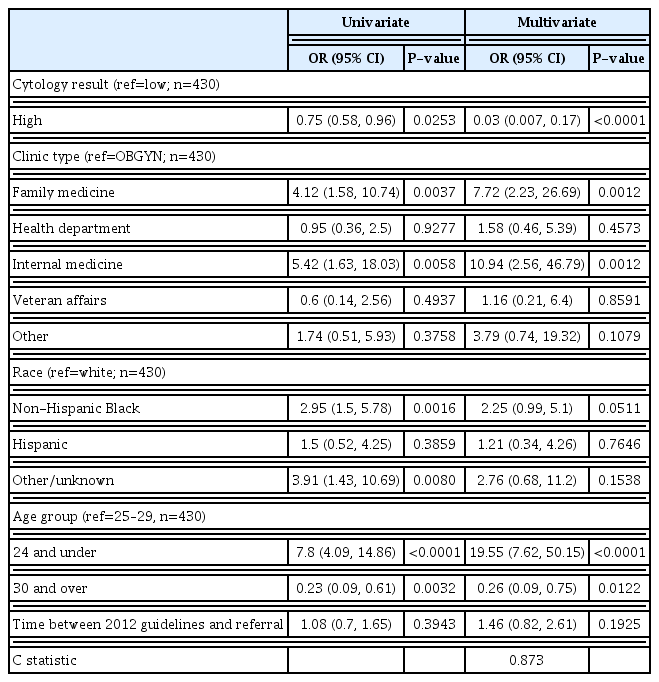

Univariate logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and statistical significance of discordant referrals as a function of cervical cytology and other covariates individually.

To adjust for the confounders, multivariable logistic regression analysis was used. The model estimated the likelihood and statistical significance of a discordant referral as a function of cervical cytology while controlling for clinic type, race, age group, and the duration between the publication of the guidelines and referral to the VCU Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. We used the C-statistic to evaluate the strength of the model’s ability to predict outcomes similar to those observed in the study population. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NY, USA).

Results

1. Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics indicated that among the 430 patients included in the study, there were 355 (82.56%) concordant referrals and 75 (17.44%) discordant referrals (Table 1). The referrals resulted in the recommendations by the VCU physician for 340 (79.07%) colposcopies, 57 (13.02%) re-screening tests, and 35 (7.91%) LEEPs. Cervical cytology (Pap test) results with the most discordant referrals included ASCUS (29%), LSIL (48%), and NILM (20%). The VCU attending physician reviewing the referrals had a 95% adherence rate to the 2012 ASCCP guidelines. The VCU attending physician reviewing the referrals was able to identify 72% of the discordant referrals as non-adherent to the 2012 ASCCP guidelines. Three patients were correctly referred by the outside providers and the reviewing VCU physician recommended repeat screening in 1 year if they had a history of abnormal Pap test or colposcopy findings. Altogether, 18 patients (4.17%) did not receive post-colposcopy recommendations for follow-up testing from the VCU physicians, which were concordant with the 2012 ASCCP guidelines. Among these, six patients (33%) had previous discordant referrals for colposcopy and were subsequently provided follow-up testing recommendations by the VCU physicians, which were not concordant with the 2012 ASCCP guidelines. Family medicine providers and health departments accounted for 40% and 28% of the discordant referrals, respectively. Approximately 51% of the study population was African American, 31% of the study population was white, and 11% of the study population was Hispanic. All variables showed statistically significant differences between the concordant and discordant referrals (Table 1).

Table 2 has described the distribution of discordant referrals by age group. There were 31 (41%) discordant referrals among patients aged 21–24 years. Among these, the Pap test results indicated ASCUS in six patients (19%), LSIL in 24 patients (77%), and NILM in one patient (0.3%). For discordant referrals in this age range, significant differences were observed in the HPV test results among the cervical cytology categories. However, no statistically significant differences were noted in other variables.

Descriptive statistics regarding discordant referrals according to cervical cytology results and ASCCP age group recommendations

There were five discordant referrals in the age group of 25–29 years including one patient with ASCUS and the remaining four with NILM. Altogether, 39 patients (52%) in the age range of 30–64 years had discordant referrals with Pap test results indicating ASCUS in 38 %, LSIL in 31%, HSIL in 5%, and NILM in 26% of the patients. Notably, four patients were categorized as discordant LSIL referrals if HPV co-testing was negative.

Among the patients aged 21–24 years and having discordant LSIL referrals, seven patients subsequently underwent non-indicated colposcopies at the VCU (not included in the table). Furthermore, two of these patients underwent LEEP, as colposcopy for LSIL at the age of 21–24 years resulted in cervical intraepithelial dysplasia (CIN) II or CIN III. The most common discordant factor with respect to the ASCUS referrals was that co-testing for high-risk HPV subtypes was negative (n=7). Seven women aged 21–24 years with ASCUS cytology and a positive HPV test were referred for colposcopy instead of repeat cytology in 1 year. Additionally, seven referrals for ASCUS cytology did not have any co-testing or reflex testing.

In addition to the aforementioned findings, 10 patients were referred for the cervical cytology results of samples collected from the vaginal cuffs despite prior hysterectomies performed for benign lesions. Two of these patients had HSILs. Both patients with HSILs underwent examination by the VCU providers. One patient underwent colposcopy and pathological examination of the biopsy specimens indicated low-grade vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN 1). The VCU provider recommended repeat contesting in 1 year in accordance with national comprehensive cancer network guidelines suggesting that VAIN 1 can be observed carefully without ablative or surgical treatment, since the lesions often regress spontaneously. In the other patient with HSIL of the vaginal cuff, colposcopy was performed without biopsies and recommendations were made for a clinic visit in 12 months for examination of the vaginal cuff by a trained gynecologist.

Additionally, eight patients with the first occurrence of HPV positivity on screening and the presence of NILM were referred instead of recommending co-testing in 12 months. Two patients aged below 30 years and having NILM/HPV positivity were referred for co-testing. Three patients were referred despite normal cytology and negative HPV testing results. Two patients were referred for NILM/HPV positivity, but screening was performed at an incorrect interval.

2. Simple and multivariable logistic regression

After controlling for other covariates, the adjusted model resulted in a decreased likelihood of a discordant referral for patients with high-grade lesions (ASCH/AGC/HSIL) (OR, 0.03; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.006–0.166; P<0.001) when compared with those with low-grade lesions (ASCUS/LSIL/NILM) or no lesions. These results suggest that patients with low-grade lesions were 97 times more likely to be incorrectly referred for colposcopy. The adjusted odds of a discordant referral for high-grade lesions were much lower than the odds of a discordant referral for high-grade lesions in the univariate regression (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.58–0.96; P<0.05). The likelihood of a discordant referral from a family medicine provider (OR, 7.72; 95% CI, 2.23–26.69; P<0.01) and internal medicine physician (OR, 10.94; 95% CI, 2.56–46.79; P<0.01) compared to an obstetrician/gynecologist was also much higher in the adjusted model when compared with the likelihood of a discordant referral from a family medicine provider (OR, 4.12; 95% CI, 1.58–10.74; P<0.01) or an internal medicine physician (OR, 5.42; 95% CI, 1.63–18.03; P<0.01) in the unadjusted model. The likelihood of a discordant referral in patients aged below 24 years (OR, 19.55; 95% CI, 7.62–50.15; P<0.001) compared to women aged 25–29 years was much higher in the adjusted model than in women aged under 24 years (OR, 7.80; 95% CI, 4.09–14.86; P<0.001) in the unadjusted model. The likelihood of an incorrect referral for non-Hispanic black patients was significantly higher (OR, 2.95, 95% CI, 1.5, 5.78, P<0.01) in the unadjusted model but not significantly higher in the adjusted model. The multivariate logistic regression model strongly predicted similar rates of correct referrals when compared with those observed in the sample (C-statistic, 0.873) (Table 3). The show rate for patients correctly referred from outside institutions for colposcopy or LEEP was 83.2%.

Discussion

Cervical cancer screening and appropriate referral for biopsy or excision have greatly decreased the associated mortality in the USA [9]. However, the effectiveness of the ASCCP guidelines depends on the knowledge and adherence of the providers to these guidelines. Our study demonstrates that 17.4% of the referrals for colposcopy to a tertiary academic center were discordant with the 2012 ASCCP guidelines. Although most of the referrals to the tertiary center were concordant with the published guidelines, there is still room for improvement. We also identified the factors associated with referrals that were non-adherent to the 2012 ASCCP guidelines.

Women with low-grade lesions (ASCUS, LSIL, and NILM) were more likely to be referred without adhering to the guidelines. Our results indicated that high-grade lesions were easier to interpret, since they always required diagnostic testing and practitioners understood that HSIL, ASC-H, and AGCs with undetermined significance required follow-up.

Patients aged 21–24 years or 30–64 years were more likely to be incorrectly referred when compared with those aged 25–29 years. This possibly reflects the simplicity of guidelines in the age group of 25–29 years, as HPV only comes into account when it is reflexed for ASCUS. The 2012 guidelines extended the adolescent guidelines to the age of 24 years with the understanding that HPV infection is common in this age group and dysplastic lesions are most likely to resolve without intervention [10]. Patients aged 25–29 years who have LSILs are referred regardless of the HPV status, while those aged 21–24 years who have LSILs should undergo repeat cytology after 12 months. Furthermore, HPV infection is known to be necessary for the development of cervical cancer and the 2012 guidelines specifically address how to approach discordant cytology screening results such as HPV negativity or LSIL [11,12]. Similar to previous studies that indicated a lack of knowledge and adherence to the screening intervals recommended by the ASCCP, our study suggests that there is confusion regarding the interpretation of cytology results specifically among women aged 21–24 years and among cases with discordant cytology and HPV status including HPV negativity and LSIL [7,8].

A patient who underwent a screening test at a family medicine or internal medicine clinic is more likely to be incorrectly referred. This may reflect the tendency of family medicine and internal medicine providers for incorrect referrals, since they are not familiar with the guidelines or with the use of online applications. This “gap” in knowledge should receive continuous focus. Furthermore, the present study indicated that in our region, health departments tend to follow the ASCCP recommendations closely. Education should focus on increasing the knowledge about the online applications among our colleagues who are not obstetricians/gynecologists and informing the practitioners when referrals do not adhere to the guidelines.

Primary vaginal cancer is very rare and the collection of cytology specimens from the vaginal cuffs is not recommended for women who never had CIN 2 or higher grade of dysplasia or for those who underwent hysterectomy for benign lesions [13]. In our study, multiple patients were referred for cervical cytology results of samples collected from the vaginal cuffs despite hysterectomies performed for benign lesions. As observed in our study, patients with prior hysterectomies are not only incorrectly screened but also referred for un-indicated procedures. Interestingly, two patients were referred for HSIL of the vaginal cuff. Since both of these patients had low-grade or no abnormal findings, we believe that they were inappropriately screened. A survey performed in 2015 revealed that approximately 14% of the advanced nurse practitioners routinely collected cytology samples from the vaginal cuffs and 8% were unsure whether patients who had a hysterectomy for benign lesions should undergo cytological screening [8].

Notably, African American patients accounted for the majority of our patient population and exhibited a trend toward the likelihood of incorrect referrals when compared with White or Hispanic patients although the difference was not statistically significant in the adjusted model. This finding might indicate an underlying bias. Our study also indicated that there was no change in the referral accuracy over a 2-year period.

To the best of our knowledge, no other study has evaluated the adherence to referral guidelines for biopsy or excision. The strengths of this study include the varied clinical subspecialties that referred the patients to a large academic center for colposcopy and LEEP. The study also has some limitations. It did not identify patients who had a pathology that should have been referred, but were returned to routine screening. The study evaluated referrals to a single center and had a small sample size of 430.

Future research in this field could include a review of all cytological tests to identify patients who should have been referred for colposcopy, but were returned to screening instead. Future research could also include surveys to identify whether providers are aware of the changes in colposcopy guidelines, studies regarding the availability of a mobile application for interpretation and guidelines, and questionnaires regarding the knowledge of current guidelines. We could also expand data collection to include referrals from 2013 to date and re-evaluate whether there has been any change over time in referral concordance. Education and vigilance regarding evidence-based algorithms must continue to receive constant focus. Changes in the cervical cancer screening guidelines have been published in 2020 and 2019 ASCCP guidelines have transitioned from result-based algorithms to risk-based algorithms. However, the algorithms for the age group below 25 years have been carried forward [6].

Our results indicate that patients from this age group were incorrectly referred even when HPV infection had a high probability of regression. Future studies could evaluate referral concordance over time, especially among patients aged <25 years. Our results also indicate that some providers, especially those belonging to the fields other than gynecology, may not consider the necessity of HPV infection for the development of cervical cancer or the lack of need for screening in cases of hysterectomy performed for benign lesions while referring patients for colposcopy. Referrals not adhering to the evidence-based guidelines may lead to unnecessary procedures especially among patients of reproductive age, increased patient stress, and added healthcare expenses.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Elizabeth King, MD (Department of Pediatrics, Mayo Clinic School of Graduate Medical Ed, Rochester, Minnesota) for her assistance in data collection.

This paper was presented at the 2019 ACOG Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting at the Nashville Music City Center in Nashville, TN, May 3–6, 2019.

Notes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB HM2004659) as exempt on March 3, 2018, since it reviewed already existing information and posed minimal/no risk to the subjects.

Patient consent

Informed consent was not required because this was a retrospective study.

Funding information

Services supporting this research project were generated by the VCU Massey Cancer Center Biostatistics Shared Resource, supported in part with funding from the NIH-NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016059.