A case of cystic adenomyoma of the uterus after complete abortion without transcervical curettage

Article information

Abstract

We diagnosed a 2-cm, large cystic adenomyoma after complete abortion without transcervical curettage, based on symptoms of dysmenorrhea, time of onset, and sonographic findings. The cystic adenomyoma was treated successfully with laparoscopic mass excision.

Introduction

Many women of reproductive age experience dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain. Adenomyosis is one of the most common causes of this pain. Additionally, adnenomyosis provoked infertility, dyspareunia, and frequent recurrence after treatment, so, as it know, adenomyosis is not cancer, but, cancer-like lesion.

Adenomyosis is a benign gynecologic disease resulting in globular enlargement of the uterus owing to invagination of endometrial glandular cells and stromal cells into the myometrium of the uterus. Adenomyosis usually occurs in women who have given birth and, in some cases, may be an indication for hysterectomy. Twenty percent of uterine specimens obtained after hysterectomy have diffuse adenomyosis [1]. Occasionally, a cystic lesion develops in the myometrium of a uterus affected by adenomyosis. The cyst is usually less than 5 mm in diameter and occurs mainly in multiparous women aged more than 30 years [2].

A large cystic lesion, more than 1 cm in diameter, is termed an adenomyotic cyst, cystic adenomyosis, or cystic adenomyoma [2]. This condition is very rare, with only approximately 30 reported cases to date [3].

We present a case report of a large cystic adenomyoma in a uterus without diffuse adenomyosis without transcervical curettage. This adenomyoma was the cause of severe, intractable dysmenorrhea; it was diagnosed using transvaginal ultrasonography and was successfully excised laparoscopically.

Case report

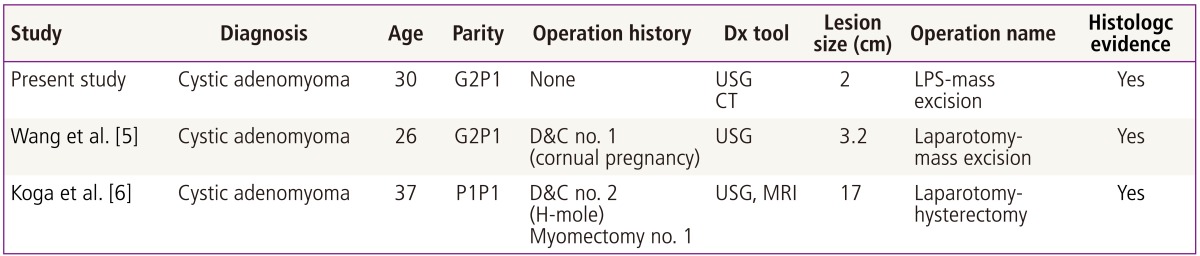

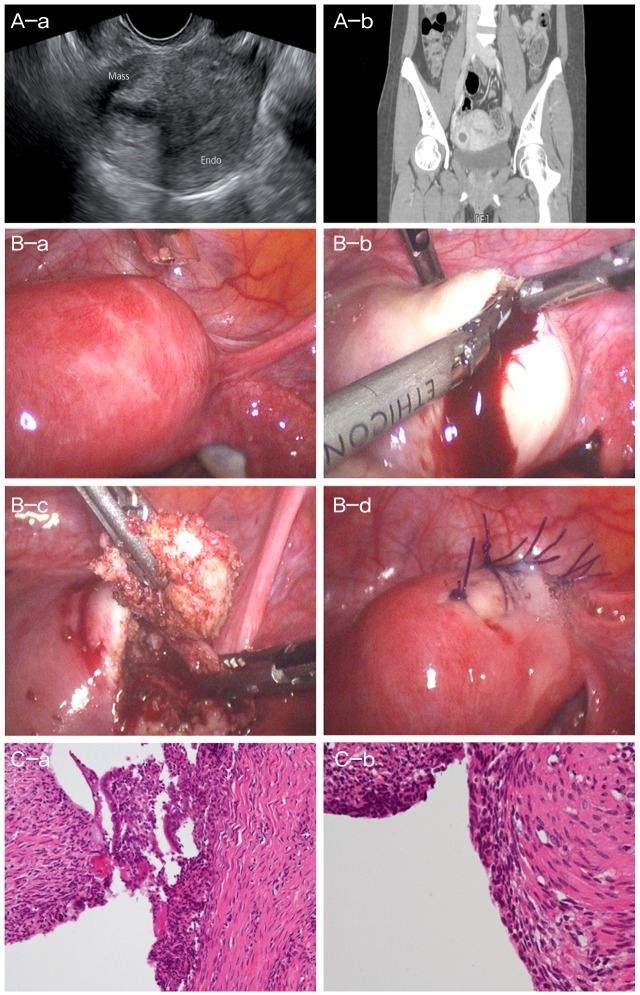

A 30-year-old woman (gravida 2, para 1, and abortion 1) was referred to the emergency room of our tertiary center because of severe, progressive, and intractable dysmenorrhea for 1 year. Abdominal discomfort began on the third day of her menstrual cycle, accompanied by cramping pain, syncope, headache, and cold sweats. Her pain was not relieved by medication, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and oral contraceptive pills. Her menarche had occurred at the age of 14 years, and she had no specific problems with secondary sexual development. Her menstrual cycle was regular (28 days) with a duration of 5 days and moderate bleeding. She had no dysmenorrhea prior to 1 year previously when this episode began. Four year ago, she had a natural singleton pregnancy, which culminated in the natural vaginal delivery of a full-term boy. Approximately 1 year previously, she was pregnant. However, at GA 6 weeks, she underwent a complete abortion spontaneously without any transvaginal procedures such as transcervical curettage. After the abortion, severe dysmenorrhea began and progressively increased. On physical examination, the pain localized to the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, and no tenderness to palpation or rebound tenderness was observed. Bimanual pelvic exam revealed a non-mobile, small, palpable mass on the right side of the uterus. Laboratory findings, including level of CA-125 (17 U/mL), were normal. Serum human chorionic gonadotropin level was near zero. Transvaginal sonography performed using a Volusion 730 Pro scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) showed a normal sized uterus, unremarkable endometrium, and intact ovaries. However, a 2×2 cm hypoechoic mass surrounded by a hyperechoic enhancing rim was seen on the anterior wall of the right side of the uterus. Within this mass, an inner hypoechoic cystic lesion measuring approximately 1.2×0.8 cm was seen (Fig. 1A-a). The mass had no communication with the endometrium. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a 2×2 cm mass on the uterine side of the uterus with an approximately 1.2-cm cystic area inside the mass (Fig. 1A-b). The appendix was intact. No associated urogenital anomalies were detected. We believed that this condition represented a cystic adenomyoma in light of our previous case report [1], and elected to perform laparoscopic excision of the mass.

(A-a) Sonographic finding of cystic adenomyoma. (A-b) Computed tomography scan of cystic adenomyoma. Histologic finding. A central cyst wall is lined by endometrial glandular epithelium and endometrial stromal cells within myometrium. Surrounding myometrium reveals smooth muscle proliferation forming myomatous mass. Laparoscopic mass excision. (B-a) Cystic adenomyoma at right fundal area, before vasopressin injection. (B-b) After incision, chocolate-colored fluid leakage from cystic adenomyoma. (B-c) Mass excision. (B-d) Suture. Histologic finding. A central cyst wall is lined by endometrial glandular epithelium and endometrial stromal cells within myometrium. Surrounding myometrium reveals smooth muscle proliferation forming myomatous mass. (C-a) The cyst wall is lined by single layer of flat columnar cells and underlying endometrial stomal cells which is compatible with adenomyosis (H&E, ×200). (C-b) Compatible with adenomyosis (H&E, ×400). Mass, cystic adenomyoma; Endo, endometrium.

A laparoscopy was performed on the 20th day of the patient's menstrual cycle. Under general anesthesia, she was placed in the lithotomy position. An 11-mm trocar (Excel Endopath; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) was inserted as the primary puncture after making a skin incision along the lower margin of the umbilicus. To create a pneumoperitoneum, CO2 was insufflated into pelvic cavity using a Veress needle. Subsequently, second, third, and fourth punctures using 12-mm and 5-mm trocars were carefully created in the left upper quadrant (umbilicus level), right lower quadrant, and lower midline area of the abdomen. A uterine manipulator was inserted to easily handle the uterus and adnexa.

The laparoscopic view showed a bulging mass measuring approximately 2×2 cm in the anterior portion of the right side of the uterus; the mass appeared to be a myoma (Fig. 1B-a). After direct injection of diluted vasopressin (vasopressin 10 units diluted in 100 mL of normal saline) into the uterine mass, an oblique incision was made using monopolar cautery. During enucleation of the mass, chocolate-colored fluid leakage, consistent with an endometrioma, was seen (Fig. 1B-b); the fluid was drained from the cystic portion of the mass (Fig. 1B-c). A harmonic scalpel and a 10-mm screw were used for complete excision of the mass. The excision site was closed with interrupted endosutures using 1-0 monofilament (Fig. 1B-d). Infusion of methylene blue dye through a uterine manipulator showed no communication between the mass and endometrial cavity. Operative time was 70 minutes, and estimated blood loss was less than 20 mL. There were no intraoperative or postoperative adverse events, and the patient was discharged 48 hours after surgery in good condition.

On macroscopic examination, the mass measured 2×2 cm in diameter. The inner surface of the mass contained a brownish discolored layer with the appearance of an ovarian endometrioma. Histological examination showed that the central cyst wall was lined with endometrial glandular epithelium and endometrial stromal cells within myometrium, and the surrounding myometrium revealed smooth muscle proliferation forming a myomatous mass compatible with an adenomyosis (Fig. 1C). In the 2 years since the surgery, the patient has had regular menstruation with no dysmenorrhea.

Discussion

Cystic lesions in the uterus are generally pregnancy-related, such as a cornual pregnancy, cystic degeneration of a leiomyoma, a uterine anomaly such as a bicornuate uterus, or cystic adenomyoma [3]. A cystic lesion arising from the myometrium of the uterus, such as a cystic adenomyoma, is classified either as juvenile type, when it is the result of uterine anomaly, or adult type, such as a rare adenomyotic condition [1]. Both types of cystic adenomyoma are characterized by progressively intractable dysmenorrhea owing to estrogen-induced proliferation of ectopic endometrial glands and stromal cells within the myometrium. This is similar to eutopic endometrium, especially during menstruation, when a blood-filled cavity similar to an endometrioma presses against the surrounding myometrium. A juvenile cystic adenomyoma is caused by a congenital defect of the Mullerian duct during fetal development, resulting in dysmenorrhea beginning at young age, usually soon after menarche. In 2010, Takeuchi et al. [4] proposed the following diagnostic criteria: 1) age ≤30 years; 2) cystic lesion of ≥1 cm in diameter independent of uterine lumen and covered by hypertrophic myometrium on images; and 3) association with severe dysmenorrhea [1]. In contrast, the adult type is a variant of adenomyosis, caused by giving birth or gynecologic procedures, such as cesarean section, myomectomy, and transcervical curettage [5]. Generally, the cyst is less than 5 mm in diameter and occurs in association with diffuse adenomyosis of the uterus [4].

A search in PubMed for the terms "cystic adenomyoma," "adenomyotic cyst," and "cystic adenomyosis" brought up several papers on adult cystic adenomyoma (Table 1).

In 2007, Wang et al. [5] reported a large cystic adenomyoma in a woman who had a cornual pregnancy, Methotrexate injection, and suction curettage. He proposed that invasive procedures such as curettage caused disruption between the basal endometrial layer and myometrium, thus leading to cystic adenomyoma.

Koga at al. [6] presented a rare case report about huge cystic adenomyosis. The patient was 37 years of age and had undergone several uterine procedures such as 2 myomectomies and 2 dilatation and curettage procedures for H-mole. She reported abdominal cramping pain. On evaluation, a large cystic adenomyosis measuring 17×11×8 cm was detected. She underwent hysterectomy. The authors concluded that repeated uterine surgical interventions caused cystic adenomyosis.

In our case, we diagnosed a 2-cm, large cystic adenomyoma based on symptoms of dysmenorrhea, time of onset, nature of the pain, and sonographic findings of a hypoechoic cystic mass surrounded by a hyperechoic outer rim. The adenomyoma was treated successfully with laparoscopic mass excision. The diagnosis of cystic adenomyoma was eventually confirmed by pathological examination. Several factors led us to consider cystic adenomyoma as the cause of the pain before surgery. First, the patient had never experienced such severe dysmenorrhea before the complete abortion; however, after the event, she reported progressive, intractable pain with the maximal tender point at the same point as a cystic lesion. Second, her pain began on the third or fourth day of her menstrual cycle unlike conventional dysmenorrhea, which generally begins on the first or second day of the cycle. Third, on sonographic imaging, the lesion had the appearance of an endometrioma or hemorrhagic cyst of the ovary. We believe that this is the first case of a cystic adenomyoma following complete abortion without surgical procedures in normal pregnancy.

In pregnancy, the implantation site of oocyte have special changes, morphologically and functionally. All perfect process is necessary for successful pregnancy. But, In this patient, because of the problem of implantation or genetic defect of oocyte, for whatever reason, she experienced a complete abortion. After abortion, during regeneration process of endometrial stromal and gland cell, maybe there will be an invagination of endometrial cell in especially weak endometrial defect although there is no transcervical procedure.

In the present case, the patient experienced progressive and intractable dysmenorrhea for 1 years. She visited the emergency room several times because of the pain, and she was prescribed NSAIDs and oral contraceptives for cystic degeneration of a myoma. Our findings show that in a woman aged more than 30 years with severe dysmenorrhea and a cystic lesion in the uterus on sonography, the diagnosis of cystic adenomyoma must be considered.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.