Effect of bupivacaine versus lidocaine local anesthesia on postoperative pain reduction in single-port access laparoscopic adnexal surgery using propensity score matching

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The umbilicus is a single, painful incisional site on the abdomen during trans-umbilical single-port access laparoscopic surgery. Previously, we found that periumbilical lidocaine could reduce postoperative pain. This study aimed to compare the efficacy of bupivacaine and lidocaine in reducing pain.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis in a study group (Bupivacaine group, 100 patients who received periumbilical infiltration of bupivacaine before their incisional site repair completion) and control group (Lidocaine group, 100 patients who received lidocaine at their incisional site repair completion). We compared postoperative pain based on the numerical rating scale (NRS) between propensity score-matched Bupivacaine-treated (n=50) and Lidocaine-treated (n=50) patients.

Results

The postoperative pain scores based on the NRS were not significantly different between the 2 groups until 12 hours post-operation. However, 24 hours post-operation, the Bupivacaine group showed significantly lower pain than the Lidocaine group (24 hours, 1.76±1.07 vs. 2.53±1.11 NRS, P<0.001; 48 hours, 0.84±0.85 vs. 2.16±0.85 NRS, P<0.001).

Conclusion

Periumbilical infiltration of bupivacaine has a longer acting efficacy on reducing postoperative surgical pain than that of lidocaine.

Introduction

Gynecologists have adopted laparoscopic procedures because of their advantages, including decreased postoperative pain and bleeding, shorter hospitalization, and faster recovery times [1]. Further, innovations in laparoscopic surgical equipment and techniques have led to the application of single-port access (SPA) laparoscopy in the field of gynecology [23].

SPA laparoscopy results in reduced trauma to the abdominal wall and improved cosmetic effects compared with those achieved using conventional multiport access laparoscopy [4]. One of the most expected advantages of SPA laparoscopic surgery may be reduced postoperative pain with a single-site incision, as well as improved cosmesis. However, there is no consensus on whether SPA laparoscopic surgery reduces postoperative pain compared with conventional multi-port laparoscopy [45678910].

Of note, the umbilicus is a single, painful incisional site on the abdomen in trans-umbilical SPA laparoscopic surgery. Previously, it was reported that periumbilical infiltration of lidocaine (2% lidocaine hydrochloric acid with epinephrine 1:100,000) during incisional site (umbilicus) repair was significantly associated with decreased postoperative pain immediately after the surgery and at 6 hours post-operation [11].

However, the pain-reducing efficacy wears off after 6 hours post-operation, and patients may experience pain afterward. The effect of bupivacaine is known to last much longer than that of lidocaine [12]. We conducted a study to compare the pain-reducing degree obtained after repair of the surgical site using 1% lidocaine versus 0.25% bupivacaine, a long-acting local anesthetic.

Materials and methods

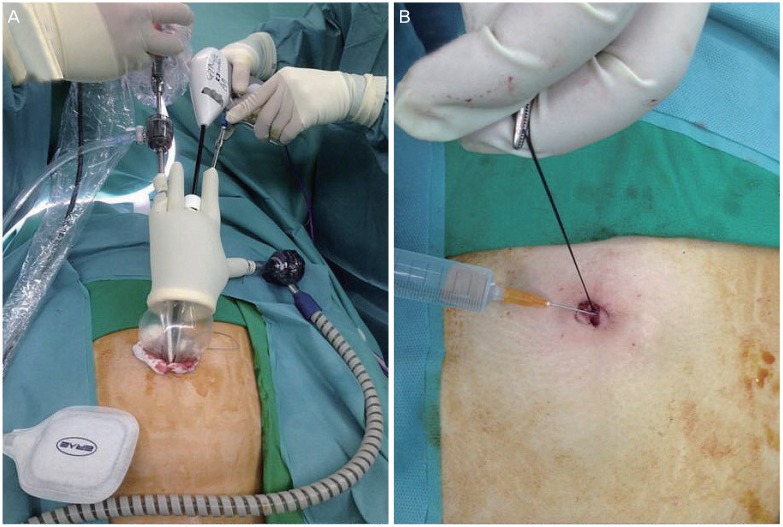

A total of 200 patients who underwent trans-umbilical SPA laparoscopic adnexal surgery from 2012 to 2018 were retrospectively recruited, as a segment of an Institutional Review Board-approved study. During SPA laparoscopic adnexal surgery (Fig. 1A), the study group (100 patients) received periumbilical infiltration of 25 mg bupivacaine subcutaneously (Fig. 1B), whereas the control group (100 patients) received 30 mg lidocaine with epinephrine during the repair of the umbilical incision. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) elective adnexal surgery for benign lesions, 2) adequate medical condition (American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System 1–2) of the patient, 3) no evidence of gynecologic malignancy on imaging studies, and 4) CA-125 ≤150 IU/mL [11]. For the exclusion criteria, we selected the following to focus primarily on evaluating postoperative pain along with surgical outcomes: 1) the presence of additional procedures, such as endometrial curettage, hysteroscopy, or myomectomy, at the time of adnexal surgery, and 2) conversion of SPA laparoscopic cases to conventional laparoscopy.

Umbilical infiltration of local anesthesia while single-port access (SPA) laparoscopic surgery. (A) SPA laparoscopic surgery, (B) umbilical infiltration of local anesthesia.

We used a numerical rating scale (NRS) to measure the postoperative pain level. Patients were asked to grade their pain level on a range from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates the worst pain possible, immediately after surgery in the recovery room and at 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours after surgery. Intraoperative analgesics consisted of intravenous fentanyl (100 μg) and ketorolac tromethamine (60 mg). Postoperatively, intravenous pain control was performed on demand with ketorolac tromethamine (60 mg). Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were administered 3 times daily during hospitalization when the patient began diet intake around postoperative day 1 or 2, and a 5-day discharge medication was prescribed.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 23 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify standard normal distributional assumptions. Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare continuous variables, and differences between proportions were compared using Fisher's exact test or the χ2 test. We performed propensity score matching to reduce the bias in the estimate of the difference in surgical outcomes of the 2 groups. The propensity score model was devised accounting for age, body mass index (BMI), operation history, pathologic diagnosis, and adhesion. The propensity score model was well-calibrated. Based on the propensity scores, 50 patients who underwent bupivacaine infiltration were matched to 50 patients who underwent lidocaine infiltration. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

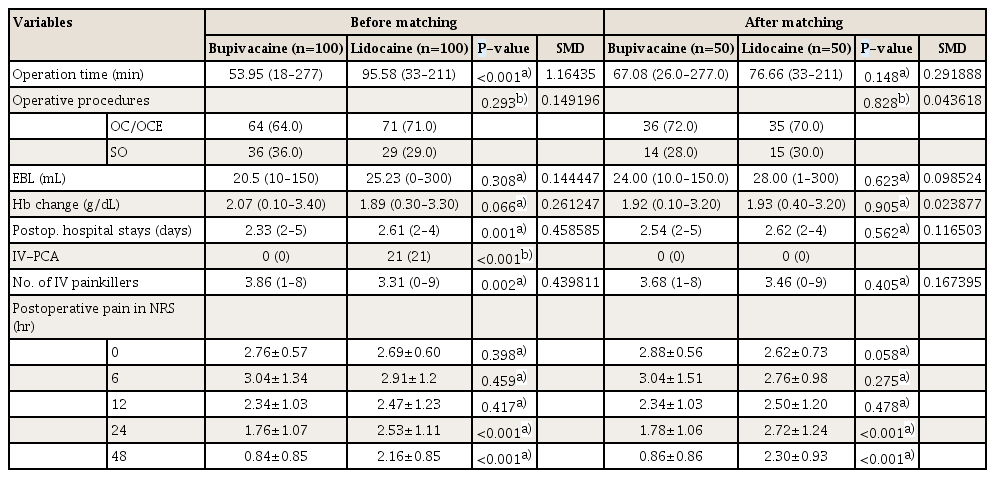

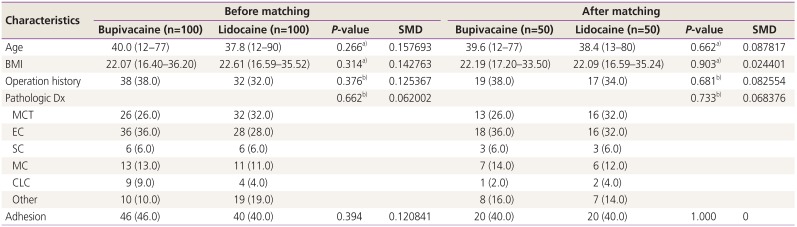

The patient characteristics by group and propensity score matching are shown in Table 1. A total of 200 patients were enrolled in the Bupivacaine group and Lidocaine group. None of our patients complained of any side effects of local injection at the application sites such as blistering, itching, swelling, or reddening of the skin. The median age was 39.97 years (range, 12–77 years) in the Bupivacaine group and 37.83 years (range, 12–90 years) in the Lidocaine group. The histopathologic diagnosis of the patients included mature cystic teratoma, endometriotic cyst, serous cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenoma, corpus luteal cyst, and others. The 50 paired patients were selected by propensity score matching. With the propensity score matching, the age (2.14 to 1.24), BMI (0.54 to 0.10), operation history (7% to 4%), pelvic adhesions (6% to 0%), and pathologic diagnosis differences between the Bupivacaine group and Lidocaine group declined.

We compared the surgical outcomes of the 2 groups (Table 2). The surgical procedures performed in this investigation were adnexal surgeries, including an ovarian cystectomy or enucleation and salpingo-oophorectomy. After the propensity score matching, operation time, operative procedures, blood loss, hemoglobin change, postoperative hospital stay, intravenous patient-controlled anesthesia, and several intravenous analgesics were not significantly different between the 2 groups.

Fig. 2 shows the postoperative pain in NRS as a function of time for matched patients receiving the bupivacaine and lidocaine. The postoperative pain scores based on the NRS were not significantly different between the 2 groups until 12 hours post-operation. However, starting from 24 hours post-operation, the Bupivacaine group showed significantly lower pain compared with the Lidocaine group (24 hours, 1.76±1.07 vs. 2.53±1.11 NRS, P<0.001; 48 hours, 0.84±0.85 vs. 2.16±0.85 NRS, P<0.001).

Discussion

In this study, we compared the efficacy of periumbilical infiltration of bupivacaine vs. lidocaine as an adjuvant agent for reducing postoperative pain after gynecologic SPA laparoscopic adnexal surgery. We found that periumbilical infiltration of bupivacaine during incisional site (umbilicus) repair was significantly associated with lesser postoperative pain at 24 and 48 hours post-operation than that of lidocaine. Prior to 12 hours post-operation, there was no significant difference in postoperative pain.

Low postoperative pain is one of the most important expectations of patients who receive SPA laparoscopic surgery. However, even with a minimally invasive approach, patients could still experience immediate postoperative pain, resulting in a delay of discharge after surgery, a slower return to routine activities and work, and increased or prolonged use of analgesics. Additionally, a prolonged hospital stay also increases health-care costs. Thus, the development of an effective technique to alleviate pain immediately after SPA laparoscopic surgery is necessary.

Despite various investigations of pain control after laparoscopic procedures, a great controversy in this field remains. Infiltration of bupivacaine into local tissues has the following advantages: effective in resolving early postoperative pain; simple and easy to use; safe when used within the margin of safety; and inexpensive, which is important especially in cases in which cost saving is a great concern [1314]. However, in a previous study, the periumbilical infiltration of lidocaine with epinephrine could alleviate surgical pain only until 6 hours post-operation [11].

The longer pain-relieving efficacy of local anesthesia is required to inhibit central sensitization and hyperalgesia [15]. Afferent nociceptive input to the spinal cord during tissue injury results in alterations in sensory processing in the spinal cord and expansion of receptive fields, which in turn lead to hyperalgesia and prolonged post-injury pain. Local analgesic administration modifies the afferent nociceptive outpouring from the site of injury, thus preventing the development of central sensitization and hyperalgesia [16].

Several studies have compared the pain-reducing efficacy of bupivacaine and lidocaine. Given the longer duration of anesthesia offered by bupivacaine, several investigators found that postoperative application after minimally invasive surgeries offered more effective postoperative pain control compared to using lidocaine only [1718192021]. To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first comparison between bupivacaine and lidocaine in gynecologic SPA laparoscopic surgery.

This study has some limitations, including its retrospective design and the small number of subjects. Additional randomized, prospective studies are necessary to confirm the advantages of the procedure. Moreover, postoperative pain is related not only to the site of trocar insertion but also to laparoscopic pain, mechanical injury, the severity of the patient's condition, and individual patient psychology. Therefore, pain assessment by individual patients using whole numbers may not represent all operation-related pain. Site-specific pain investigation could be more adequate in assessing the effectiveness of local anesthetic on the incision site. Further, the influence of epinephrine, which affects the duration of anesthetics, on the pain-relieving efficacy was not controlled because epinephrine was included only in the Lidocaine group [22]. We are planning a future study on the effect of epinephrine on both groups.

However, this study has several strengths. First, this study compared 2 SPA laparoscopic surgery groups to identify a more effective technique to improve postoperative pain. Further, all the SPA laparoscopic surgeries were performed in a single institute, thereby controlling for confounding variables such as surgical skill and postoperative care and resulting in homogeneity within the study group and control group.

In conclusion, there was a significant difference in the pain-reducing effect between 24 and 28 hours post-operation in patients treated with bupivacaine compared with that in those treated with lidocaine in SPA laparoscopic adnexal surgery. Propensity score matching was applied to control the confounding factors that could affect the differences between the 2 groups. In single port laparoscopic adnexal surgery, the administration of bupivacaine, a long-acting local anesthetic, is a more effective method for relieving postoperative pain. The use of bupivacaine infiltration for postoperative analgesia may allow the widespread use of laparoscopic day-case surgery.

Notes

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Health System (No. 4-2019-0360) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent: Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective study design.