Introduction

Although there is no scientific evidence demonstrating that female genital cosmetic surgery (FGCS) is beneficial, it has gained popularity in Korea as in many western countries [1]. The proper role of obstetrician-gynecologists should be established in this evolving field, as they have a professional and ethical responsibility to counsel patients about complications and obtain informed consent.

We report a case of a vaginal sling implantation being misdiagnosed as a rectal subepithelial tumor (SET) during a colonoscopic procedure. The patient's condition, management of the complication, and a literature review of FGCS are presented here in order to increase awareness of the risks of FGCS.

Case report

A 47-year-old woman, gravida 1, para 1, was referred for an endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) after a screening colonoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound showed a rectal SET. The patient had a history of FGCS using vaginal sling implants 9 years ago, but she did not inform the gastroenterologist of this history. She also had a surgical history of a cesarean section and an appendectomy. Her medical history was unremarkable except for taking tibolone for hormonal replacement therapy.

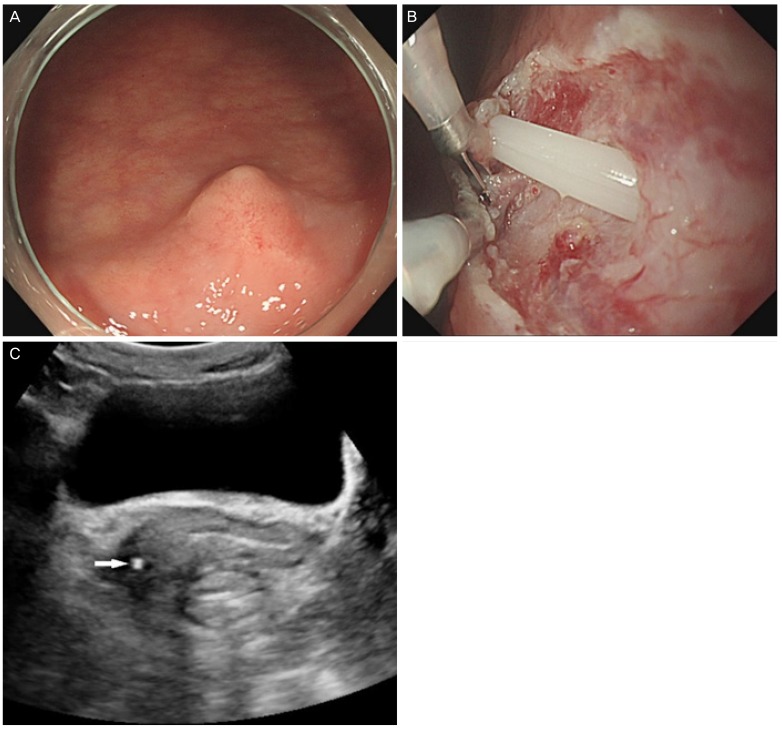

The lesion was located 3 cm from the anal verge and measured approximately 8 mm in diameter (Fig. 1A). An EMR was performed and the biopsy showed normal rectal mucosa. Endoscopic hemostasis with hemoclipping was conducted. The protruding SET lesion was still noted, and additional EMR was performed, during which an iatrogenic rectal perforation occurred revealing the tip of the silicone tube (Fig. 1B). Transvaginal ultrasonography revealed a tubular structure between the lower vagina and rectum with the tip terminating at the right vaginal wall (Fig. 1C).

Fig.┬Ā1

(A) Colonoscopy revealed a protruding lesion, which was located 3 cm from the anal verge and measured 8 mm in diameter. (B) The tip of the silicone tube was discovered due to an iatrogenic rectal perforation during the endoscopic mucosal resection. (C) Transvaginal gray-scale ultrasonography showed a tubular, echogenic structure between the lower vagina and the rectum (arrow).

The patient underwent an emergency exploratory operation under spinal anesthesia. On vaginal examination, the foreign body was felt at the 7 o'clock position in the vaginal orifice. The vaginal wall was incised and the foreign body was removed through the incision site (Fig. 2). The primary repair of the vaginal and rectal walls was performed. The patient was discharged on the 4th postoperative day, and she experienced no additional complications through her 6-month follow-up.

Discussion

In recent years, there has been an increasing number and variety of FGCS and procedures available to women [2]. The use of FGCS has provoked both ethical and scientific issues. FGCS refers to non-medically indicated cosmetic surgical procedures which change the structure and appearance of healthy external genitalia, or internally in the case of vaginal tightening [3]. A variety of procedures have been performed to improve genital appearance and enhance sexual gratification including labioplasty, clitorial hood reduction, perineoplasty, vaginoplasty, hymenoplasty, and anterior/posterior colporrhaphy [4]. The so-called ŌĆ£vaginal rejuvenationŌĆØ using sling implants is a procedure in which a sling is inserted into the vaginal wall to tighten the vaginal interior and strengthen the contractile force.

Standard medical nomenclature and procedures for FGCS have not yet been established [5], nor have proper studies been conducted assessing the rates of long-term satisfaction or safety for these procedures. More and more, plastic and urologic surgeons have joined gynecologists in performing FGCS. A survey of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons revealed that more than half (51% of the 750 respondents) offer labioplasty, but only 31.5% had received formal training for this procedure [6]. Numerous complications of FGCS have been reported, including scarring, adhesions, permanent disfigurement, infection, dyspareunia, altered sexual sensation, perineal fistula, and rectal perforation [7-9]. Many plastic and urologic surgeons are not accustomed to the vaginal approach; therefore, more complications are likely. Medical practitioners performing any FGCS should be appropriately trained. Clinicians should also discuss the risks of complications with patients before offering FGCS, and fully informed consent can only be obtained with accurate information. Women should also be informed of the lack of data supporting the efficacy of these procedures. Finally, physicians should educate patients about the importance of reporting a history of FGCS prior to undergoing surgical or endoscopic procedures to avoid misdiagnoses and unnecessary treatment.

The consensus on FGCS is constantly changing. Internationally, a number of gynecologists have opposed FGCS, expressing concern about women's motivation for seeking surgery, the efficacy and safety of these procedures, and the potential to further traumatize patients who are anxious or insecure about their genital appearance or sexual function [10]. For the physician offering FGCS, the patient's safety must be paramount. More studies are needed to provide women with accurate information regarding the short- and long-term outcomes of these FGCS procedures.