|

|

- Search

| Obstet Gynecol Sci > Volume 57(5); 2014 > Article |

Abstract

Methods

One hundred sixty-five pregnant women with myomas who delivered via cesarean section were identified. Ninety-six women had cesarean section without myomectomy, and 65 women underwent cesarean myomectomy. We compared the maternal characteristics, neonatal weight, myoma types, and operative outcomes between two groups. We further analyzed cesarean myomectomy group according to myoma size. The large myoma was defined as myoma >5 cm in size. The maternal characteristics, neonatal weight, and myoma types were compared between two groups. We also compared the operative outcomes such as preoperative and postoperative hemoglobin, operative time, and hospitalized days between two groups.

Results

There were no significant differences in the maternal characteristics, myoma types, neonatal weight and operative outcomes between cesarean section without myomectomy and cesarean myomectomy. The subgroup analysis according to myoma size (>5 cm or not) in cesarean myomectomy group revealed that there were no significant differences in the mean hemoglobin change (1.2 vs. 1.3 mg/dL, P=0.6), operative time (90.5 vs. 93.1 minutes, P=0.46), and the length of hospital stay (4.7 vs. 5.2 days, P=0.15) between two groups. The comparison of maternal characteristics, neonatal weight, and myoma types between two groups also showed no statistical significance.

Uterine myomas are the most common benign tumors of female reproductive tract, and the prevalence of myomas in pregnancy has been reported to be 2% to 5% [1,2]. The incidence of myomas rises with advancing age. Therefore, pregnant women with myomas increase with the increase of elderly gravida [3,4,5,6,7]. Myomas during pregnancy are associated with adverse obstetric complications such as fetal malpresentation, placenta abruption, intrauterine growth restriction, placenta previa, and postpartal hemorrhage [8]. Large myomas measured >5 cm in diameter are associated with higher risk of preterm delivery, short cervix, premature rupture of membrane, postpartum bleeding and blood transfusion when compared with small or no myomas [2,9].

Traditionally, cesarean myomectomy has been regarded to be perilous because of the tendency of intractable intraoperative bleeding, and uterine atony [5,6,10]. In recent decades, however, the safety of cesarean myomectomy has been reported; some reports demonstrated that cesarean myomectomy did not increase the risk of intraopeartive hemorrhage, and uterine atony compared to cesarean section without myomectomy [11,12]. However, cesarean myomectomy in large myoma is still considered to be high risk for massive hemorrhage, uterine atony, and peripartum hysterectomy. In this study, we evaluated the safety of cesarean myomectomy in women with large myoma.

This was a retrospective cohort study. We included pregnant women with myomas who delivered via cesarean section at Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital between January 2003 and December 2010. We compared the outcome of women with cesarean myomectomy and women with cesarean section without myomectomy. The maternal demographics and characteristics on myomas were evaluated, and hemoglobin changes between preoperation and postoperation, operative time, intraoperative and postoperative complications, and hospitalized days were analyzed. We excluded women with twin pregnancy, placenta previa, placenta abruption, coagulation disorders, and previous myomectomy histories.

We further evaluated the subgroup ananlysis in cesarean myomectomy group according to the myoma size. Large myomas are defined as myomas measured >5 cm in diameter on ultrasonography [2]. Cesarean myomectomy group was divided into two groups according to myoma size (>5 cm or not). We compared the maternal characteristics, features of myomas, pregnancy outcomes, and operative outcomes between two groups.

Laparotomy was made with Pfannenstiel skin incision, and uterine incision was made using low transverse incision in most of patients. After delivery of the baby and the placenta, myomectomy was performed. A linear incision was made on the myoma using monopolar cautery and then myoma was enucleated from normal uterine muscle. Bipolar cautery was used for the intraoperative bleeding control during the myoma removal and vasoconstrictive agents were not used intraoperatively. The uterine defect was sutured in a minimum of 2 layers with absorbable 1-0 Vicryl. The uterine serosa was closed utilizing absorbable 2-0 Vicryl. Bimanual uterine compression was made to enhance the uterine contraction and intravenous carbetocin was infused intraoperatively, Oxytocin was continued intravenously during the postoperative period to prevent the massive bleeding.

Continuous data were summarized as mean┬▒standard deviation, and categoric data as number and percentage. Student t-test, and chi-square test were used to determine statistical significance. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

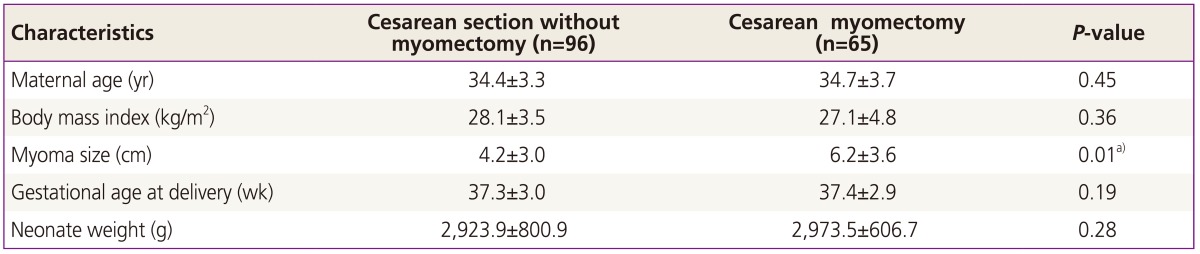

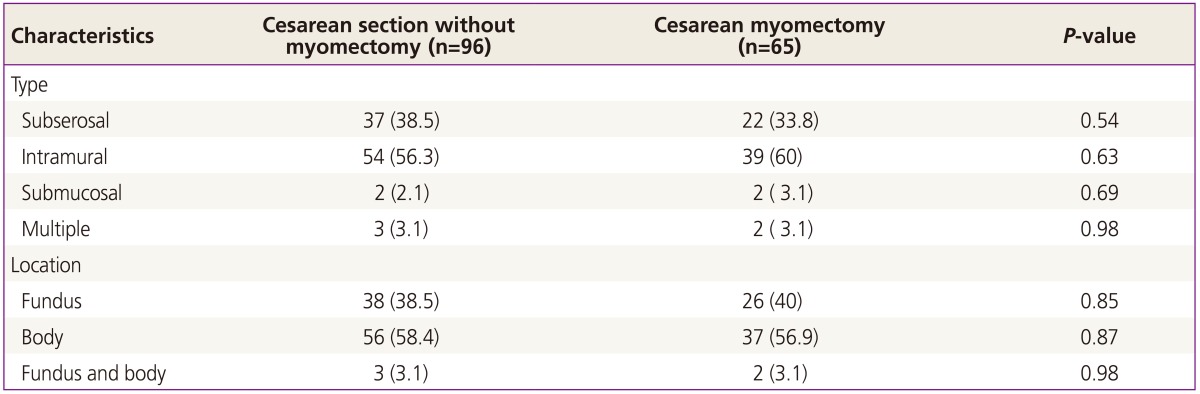

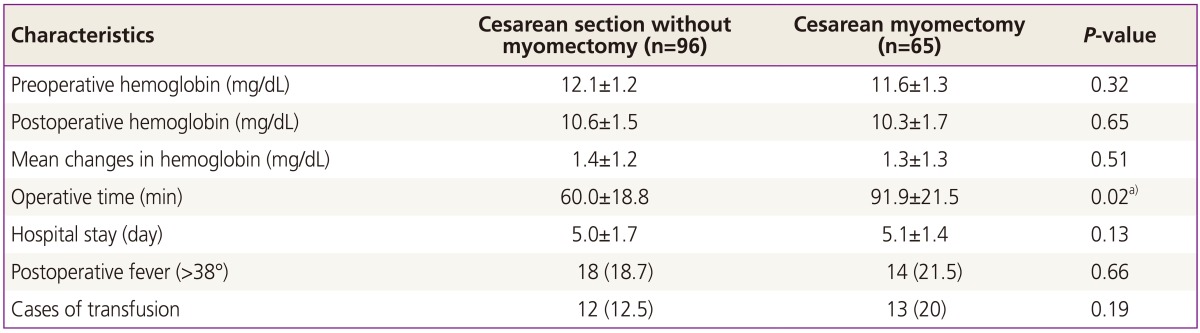

One hundred sixty-five pregnant women with myomas were identified: 96 women underwent cesarean section without myomectomy, and 65 women had cesarean myomectomy. Table 1 demonstrated the comparison of maternal characteristics and pregnancy outcomes between two groups. Cesarean myomectomy group had larger myoma compared to cesarean section without myomectomy group (6.2 vs. 4.2 cm, respectively, P=0.01), but there were no differences in gestational age at delivery and neonate weight between two groups. Table 2 showed the comparison of features of myomas between two groups: there were no differences in types and location of myomas between two groups. The operative outcomes are summarized in Table 3. The operative time of cesarean myomectomy group was significantly longer than cesarean section without myomectomy group (91.9 vs. 60.0 minutes, P=0.02). There were no differences in the incidence of postoperative fever (18.7% vs. 21.5%, P=0.66) and transfusion (12.5% vs. 20%, P=0.19) versus between two group. However, there were no differences in hemoglobin changes, and hospitalized days between two groups.

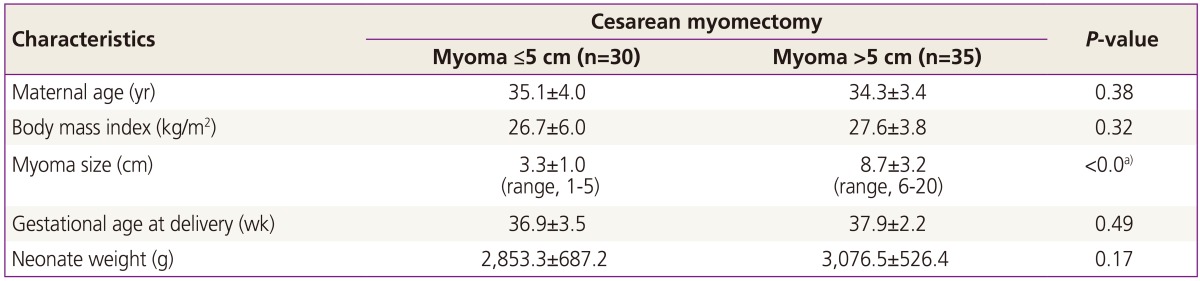

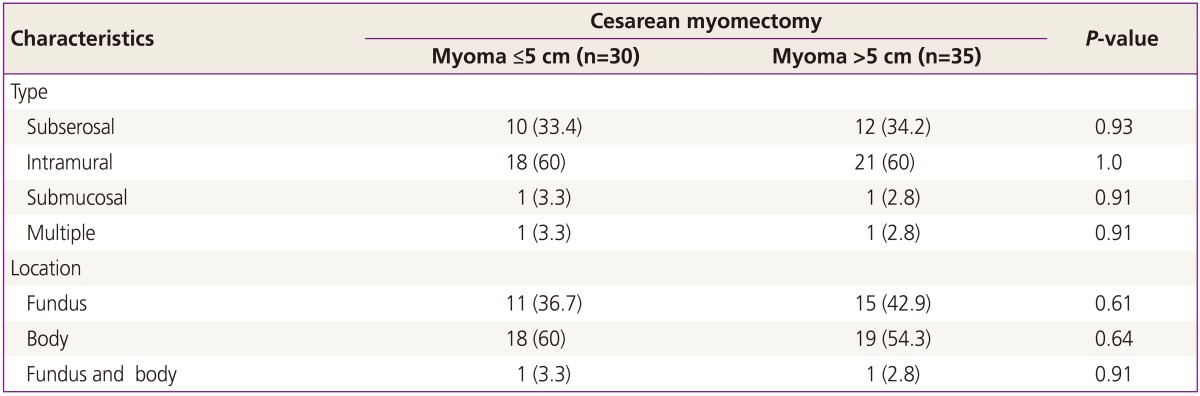

Cesarean myomectomy group was further anlayzed according to the myoma size: 30 patients had myoma sized Ōēż5 cm (A group) and the other 35 patients had myomas >5 cm (B group). Table 4 demonstrated the clinical characteristics between two groups. The average sizes of myoma differed significantly between two groups (A group 3.3 cm vs. B group 8.7 cm, P=0.01). However, There were no differences in gestational age at delivery and neonatal weight between two groups. Pfannenstiel skin incision, and low transverse uterine incision were made in most of patients. Low midline skin incision and classic uterine incision were used in only one patient with 20 cm sized myoma. There were no differences in the type and location of myomas between two groups (Table 5).

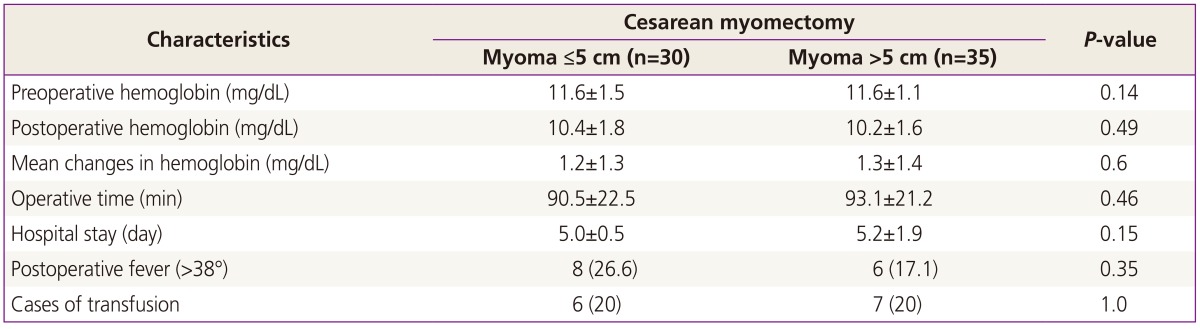

Table 6 summarized the operative outcomes of cesarean myomectomy according to the myoma size. B group (myoma >5 cm) showed no statistical differences in preoperative and postoperative hemoglobin, operative time, and hospitalized days compared to A group (myoma Ōēż5 cm). Twenty-six point six percent (8/30) of A group and 17.1% (6/35) of B group demonstrated postoperative fever. There was no difference in the incidence of postoperative fever between two groups (P=0.35). The incidence of postoperative transfusion also showed no statistical difference between two group (P=1.0). The one case of bilateral uterine artery embolization was reported in a patient with 4 cm sized myoma in A group (myoma Ōēż5 cm): uterine artery embolization was inevitable resulting from intractable bleeding over 2,000 mL and 6 pints of packed red blood cells were transfused. The successful uterine artery embolization obviated the need for hysterectomy. She was discharged in a satisfactory condition. However, there was no case of further management such as uterine artery embolization and peripartum hysterectomy resulting from postoperative heavy bleeding or uterine atony in B group (myoma >5 cm).

Cesarean myomectomy has not been performed in popular, because of the risk of copious hemorrhage and the possibility of hysterectomy [5,6,10]. If myomas are not removed, complications such as preterm labor, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, placenta previa, and postpartal bleeding cannot be prevented in the future pregnancies. Especially, large myomas >5 cm are associated with higher risk of adverse pregnancy complications such as preterm delivery, short cervix, premature rupture of membrane, postpartum bleeding when compared with small or no myomas [9]. Several authors have reported that cesarean myomectomy is safe in carefully selected cases when performed by experienced surgeons [10,13,14]. However, the safety of cesarean myomectomy in large myomas has not been thoroughly evaluated.

There are some case reports on cesarean myomectomy in large myomas. Leanza et al. [15] demonstarated a successful cesarean myomectomy in a large myoma with 22 cm in diameter, and 3,000 g in weight. Ma et al. [11] also reported that cesarean myomectomy in a 40-cm-sized myoma was uneventful after the ligation of bilateral uterine arteries for the prevention of intraoperative heavy bleeding.

In our study, we compared the operative outcomes between cesarean section without myomectomy and cesarean myomectomy in women with myomas. Even though, cesarean myomectomy group had larger average myoma size compared to cesarean section without myomectomy group (6.2 vs. 4.2 cm, P = 0.01), cesarean myomectomy group demonstrated no statistical differences in neonatal weight, gestational age at delivery, hemoglobin changes, and hospitalized days compared to cesarean section without myomectomy group. We supported that cesarean myomectomy is a safe procedure, and the result is consistent with other published papers [10,13,14].

We further anlayzed cesarean myomectomy group according to the myoma size. There have been limited case reports on cesarean myomectomy in large myomas [11,15]. Our study is meaningful, because we performed the subgroup analysis to evaluate the safety of cesarean myomectomy in large myomas. Our study supported that the large myomas (>5 cm) did not influence on any differences in preoperative and postoperative hemoglobin changes, operative time, postoperative fever, and hospitalized days, compared to those of myoma Ōēż5 cm. No one needed further uterine artery embolization or peripartum hysterectomy in cesarean myomectomy in women with myoma >5 cm. However, one patient with myoma Ōēż5 cm in cesarean myomectomy group needed postoperative uterine artery embolization resulting from intractable uterine bleeding.

Some authors supported that the specific operative techniques such as tourniquet, uterine artery ligation, and pursestring suture are helpful to limit intraoperative bleeding during cesarean myomectomy [2,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Though, we did not use forementioned techniques, double layered sutures, bimanual uterine massage, intraopeartive and postoperative uterotonic agents were effective in hemostasis regardless of the myoma size in most of patients.

In conclusion, cesarean myomectomy in large myomas is a safe procedure when performed by experienced surgeons. Obstetricians should not give up cesarean myomectomy in large myomas for the concern of the risk of uterine atony and intractable bleeding. However, there are some limitations in our study: it was a retrospective nature; we could not evaluate the subsequent pregnancy outcomes following cesarean myomectomy. Further large prospective studies are needed.

References

1. Liu WM, Wang PH, Tang WL, Wang IT, Tzeng CR. Uterine artery ligation for treatment of pregnant women with uterine leiomyomas who are undergoing cesarean section. Fertil Steril 2006;86:423-428. PMID: 16762346.

2. Vergani P, Locatelli A, Ghidini A, Andreani M, Sala F, Pezzullo JC. Large uterine leiomyomata and risk of cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109(2 Pt 1):410-414. PMID: 17267843.

3. Coronado GD, Marshall LM, Schwartz SM. Complications in pregnancy, labor, and delivery with uterine leiomyomas: a population-based study. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:764-769. PMID: 10775744.

4. Kaymak O, Ustunyurt E, Okyay RE, Kalyoncu S, Mollamahmutoglu L. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005;89:90-93. PMID: 15847868.

5. Sheiner E, Bashiri A, Levy A, Hershkovitz R, Katz M, Mazor M. Obstetric characteristics and perinatal outcome of pregnancies with uterine leiomyomas. J Reprod Med 2004;49:182-186. PMID: 15098887.

6. Davis JL, Ray-Mazumder S, Hobel CJ, Baley K, Sassoon D. Uterine leiomyomas in pregnancy: a prospective study. Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:41-44. PMID: 2296420.

7. Neiger R, Sonek JD, Croom CS, Ventolini G. Pregnancy-related changes in the size of uterine leiomyomas. J Reprod Med 2006;51:671-674. PMID: 17039693.

8. Klatsky PC, Tran ND, Caughey AB, Fujimoto VY. Fibroids and reproductive outcomes: a systematic literature review from conception to delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:357-366. PMID: 18395031.

9. Shavell VI, Thakur M, Sawant A, Kruger ML, Jones TB, Singh M, et al. Adverse obstetric outcomes associated with sonographically identified large uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril 2012;97:107-110. PMID: 22100166.

10. Ortac F, Gungor M, Sonmezer M. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1999;67:189-190. PMID: 10659906.

11. Ma PC, Juan YC, Wang ID, Chen CH, Liu WM, Jeng CJ. A huge leiomyoma subjected to a myomectomy during a cesarean section. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2010;49:220-222. PMID: 20708535.

12. Tinelli A, Malvasi A, Mynbaev OA, Barbera A, Perrone E, Guido M, et al. The surgical outcome of intracapsular cesarean myomectomy: a match control study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014;27:66-71. PMID: 23662726.

13. Sapmaz E, Celik H, Altungul A. Bilateral ascending uterine artery ligation vs. tourniquet use for hemostasis in cesarean myomectomy: a comparison. J Reprod Med 2003;48:950-954. PMID: 14738022.

14. Li H, Du J, Jin L, Shi Z, Liu M. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2009;88:183-186. PMID: 19093235.

15. Leanza V, Fichera S, Leanza G, Cannizzaro MA. Huge fibroid (g. 3.000) removed during cesarean section with uterus preservation: a case report. Ann Ital Chir 2011;82:75-77. PMID: 21657160.

17. Lee JH, Cho DH. Myomectomy using purse-string suture during cesarean section. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;283(Suppl 1):35-37. PMID: 21076924.

Table┬Ā1

The comparsion of maternal characteristics and pregnancy outcomes between cesarean section without myomectomy and cesarean myomectomy

Table┬Ā2

The comparsion of features of myomas between cesarean section without myomectomy and cesarean myomectomy

Table┬Ā3

The comparison of operative outcomes between cesarean section without myomectomy and cesarean myomectomy

-

METRICS

-

- 27 Crossref

- 2,920 View

- 43 Download

- Related articles in Obstet Gynecol Sci

-

The change of indications for cesarean section for recent 20 years.1993 July;36(7)

The Study of Obstetric Consequences of Women with Uterine Anomaly.1999 February;42(2)

The clinical study of 37 pregnancy women with aplastic anemia.1999 November;42(11)

Fertility Outcomes after Myomectomy in Infertile Patients with Myoma Uteri.2000 January;43(1)

The Prognosis of Resectoscopic Myomectomy of Submucosal Myomas.2001 June;44(6)